Many allied health, medical and nursing higher education programmes use problem based-learning (PBL) to assist future practitioners with bridging the gap between theory and practice. In 2015, a cross-disciplinary team of academic and educational design staff started to progressively transform an applied pharmacology course in a large, multi-campus undergraduate paramedicine degree. The redesign sought to more contemporaneously address learning outcomes and meet industry expectations that future paramedics would not only acquire theoretical knowledge and technical skills within their degree, but also possess non-technical skills in the areas of problem solving, decision making and reflective practice, and have a commitment to lifelong learning. These requirements are evident within accreditation frameworks for undergraduate paramedicine programmes, and reflect modern expectations of university graduates in the workplace (Hanrahan and Isaacs, 2001: 53; Council of Ambulance Authorities, 2014: 17; Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC), 2018: 4, 35).

The course redesign team formed a view that PBL techniques may help foster higher-order non-technical skills among paramedicine students within this course. PBL is a well developed, sophisticated educational approach, which has been traditionally characterised by the delivery of intentionally unstructured problems that students have to solve in groups. There are usually no lectures in traditional PBL models; instead, the ‘lecturer’ acts as a facilitator who assists learning across groups. In this way, the lecturer surrenders control of the learning process (Schwartz et al, 2001) and allows students to investigate problems, develop their knowledge and implement solutions they propose.

PBL has been described as ‘a combination of cognitive and social constructivist theories, as developed by Piaget and Vygotsky respectively’ (Ozer, 2004). Piaget and Vygotsky viewed knowledge as something that is not passively acquired; rather, they each believed that knowledge must be actively discovered and constructed by the student within dynamic social contexts.

For these reasons, PBL approaches were integrated into the practical components of this applied pharmacology course to bridge the theory-practice gap and better prepare students for safe clinical practice in the field of paramedic pharmacology intervention. After a 3-year period of progressively implementing improvements, it was realised that the approach to PBL on this course had been re-conceptualised and now ventured beyond ‘pure’ and recently described ‘hybrid’ forms of PBL (Bevinakoppa et al, 2016). In this paper, the authors describe the multi-space approach to PBL that has been developed to date, and discuss the design's place within the literature.

During this process of redesign, the course received two university teaching awards for high student satisfaction (in 2016 and 2017) and, in 2018, the redesign team received the McKeachie Award, presented by Harvard University professor James Wilkinson at the 43rd Annual Improving University Teaching Conference. Notwithstanding this, the authors conclude by noting the importance of ongoing development and rigorous evaluation of pedagogical approaches to this paramedicine course.

Methods

The educational design for this course was progressively reviewed and improved over a 3-year period. The senior lecturer in the course and the educational designer led the improvement process, which involved continued discussions between academics and practitioners from paramedic, pharmacy and learning design disciplines. Student feedback strongly influenced key design elements. Major course reviews were also carried out annually by the senior lecturer and educational designer.

This article describes the pedagogical approach currently used within this course following the 3-year review and development process. No human research data have been collected or disclosed in relation to this study so ethical approval is not required. Images are used to illustrate the approaches taken. Everyone in the images consented in writing for their photograph to be used for the purpose of describing the educational approaches used.

The focus of this article is on the influence of PBL in this course so it is outside of its scope to describe activities that are not related to PBL, such as the lecture format and the online learning environment.

Tutorial outline

Each week, students are presented with a scenario involving a patient with complex medical needs. These needs align and interact with the pharmacology content being studied in that particular week of the course.

Students work in groups to review and investigate various aspects of the scenario, resulting in a treatment plan being formed for the patient. While still in their groups, the students implement their treatment plan in a simulated paramedic setting and reflect on the outcomes of their treatment.

This approach involves students moving through physical as well as cognitive, collaborative, communication and professional practice learning spaces throughout a tutorial. In effect, they are taking a journey involving clinical theory and knowledge, social interaction, communication, problem solving and applied clinical practice.

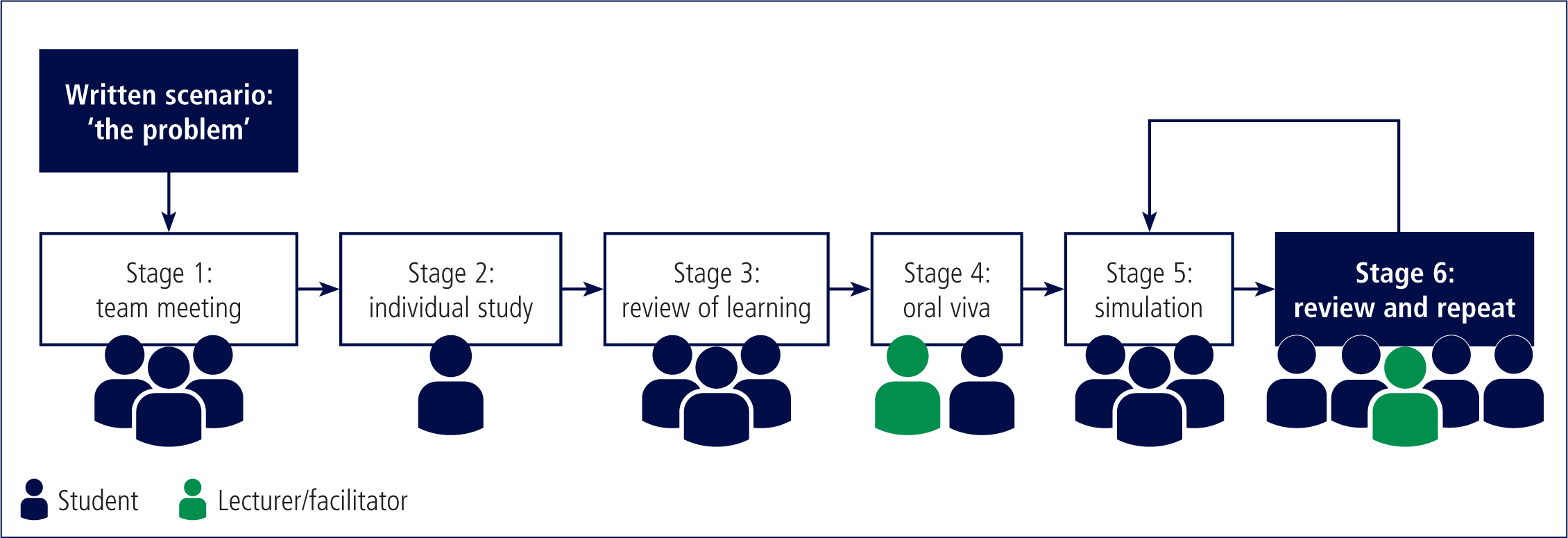

In the following sections (and for simplicity) this PBL approach is broken down and described in six chronological stages (Figure 1).

Stage 1. Team meeting

Students start the tutorial in a room that allows group work. Teams of students (about four in each team) review the written scenario, which involves a patient experiencing a particular illness or injury. A description of other factors relating to the scenario is also provided. After reading the scenario, students review a series of scenario-related questions. These questions require further investigation, so team members divide the questions between themselves, assigning about two questions per student (Figure 2).

Stage 2. Individual study

Students then start a period of individual study where they have to answer the questions they were allocated in the team meeting. They can study in the same room or in other learning spaces that will help the student with their enquiries. For example, the student may decide to study in the classroom, or make their way to the library where there is access to additional resources. Other students may prefer to retreat to an outdoor setting or even a café on the campus. What is important is that the student places themselves in a setting they believe is most conducive to effectively completing their assigned study task; these preferences will differ between individuals. The amount of study required within a short time (about 40 minutes) is significant, which means there is limited (if any) discussion between team members during this time. This reinforces the objective of fostering individual self-directed study (Figure 3).

Stage 3. Review of learning

At an allotted time, students reconvene and discuss their answers to each of the questions they were assigned. Team members discuss the way in which the questions relate to the scenario, and how the answers relate to each other. The purpose of this stage in the tutorial is for team members to learn from one another and jointly develop a comprehensive treatment plan for the patient in the scenario.

Stage 4. Oral viva

Once teams have developed their treatment plan, the lecturer draws all teams together as a group. Students then participate in an oral viva (also termed viva voce) where the lecturer asks them about the scenario, using questions that are aligned with the topics studied earlier in the tutorial.

At the beginning of the semester, the oral viva occurs in a group setting. In the first weeks, the lecturer will direct oral viva questions towards the more confident and articulate students within the class, to allow others to observe how they answer questions without notice in front of a lecturer and their peers.

As the semester continues, the oral viva questions are asked to smaller teams, then pairs, then individually between the lecturer and a student. Each stage allows students to observe others, practise their communication skills and build greater self-confidence. To facilitate this, an additional lecturer is usually required for the oral viva sessions towards the end of the semester.

Stage 5. Simulation

At the end of the oral viva process, the original team of four reconvenes in a simulation laboratory where the scenario they studied earlier is ‘brought to life’. Students are required to interact with the simulated patient and each other as they implement their treatment plan (Figure 4). The simulation itself also provides real-time repercussions, which may present new problems for students to solve collaboratively. The simulation lasts 20–30 minutes.

Stage 6. Review and repeat

At the conclusion of the simulation, all teams reconvene as a group. The lecturer discusses and debriefs the simulation and treatment plans with the group, inviting feedback and input from individual students and teams.

Key principles and lessons are highlighted by the lecturer, and discussed among the group, and experiences are shared. Students then return to the simulation room to repeat the scenario, this time performing the scenario with greater fluency.

All six stages of this PBL tutorial are completed within 3 hours. This pattern recurs each week for 8–9 weeks. Each weekly scenario presents a new patient with complex problems that align with the pharmacology topic being covered in that week of the course. Scenarios often require revision of topics from previous weeks.

Discussion

PBL has been traditionally characterised by the delivery of an intentionally unstructured problem for students to solve within a group setting. The more ‘pure’ forms of PBL require the facilitator to invest significantly in the preparation of a scenario (Tsin, 2014), while also, at the point of delivery, surrendering control over the learning elements within the PBL tutorial (Schwartz et al, 2001).

Criticisms of PBL include that its models can be too unstructured (Ward and Lee, 2002), and that personal technology use—commonly smartphones, for example—can conflict with the collaborative requirements of a PBL tutorial (Jin et al, 2015).

In this course, PBL concepts were implemented within specific learning activities and were then modified and developed over a 3-year period. The authors do not claim to have remained faithful to a traditional PBL model, nor do they claim to have invented a new model. Instead, they describe current practices within this course as a source for further reflection and enquiry.

In the model that we have described, a semi-structured problem (or scenario) is created by the facilitator. Teams of students are expected to facilitate their own learning, and an oral viva is used in the tutorial to ensure students have learned the theoretical aspects. The facilitator creates a safe learning environment, which enables students to analyse, discuss and practically implement a treatment plan, yet the student has a role to play in identifying suboptimal elements of the treatment plan which can then be addressed when the simulation is repeated. Through this process, the students' clinical reasoning process is cultivated (Barrows and Tamblyn, 1980; Delisle, 1997). Furthermore, the facilitator's role (constructing the scenario, establishing safe learning environments, and guiding oral viva activities) works in unison with the students' role (participating in the oral viva and simulation, engaging in self-directed learning, and identifying areas of suboptimal performance) to establish an effective adult learning environment (Taylor and Hamdy, 2013: 1567).

The learning outcomes for this course are able to be addressed through the modified PBL approach used within this course. These require students to obtain a detailed, theoretical knowledge of pharmacology, while gaining practical knowledge on the formulation and implementation of comprehensive pharmacological treatment plans for simulated patients (Charles Sturt University, 2019).

The modified PBL approach that has evolved within this course remains characterised by many features of traditional PBL such as student-centred, collaborative and context-specific learning (Ward and Lee, 2002). This approach is also influenced by the design team's own commitment to adult learning (including experiential learning), peer learning (including formative assessment) and lifelong learning (including reflective practice). These are discussed in the next section.

Adult learning, including experiential learning

The inclusion of a student-centred learning approach in this course is probably best described by Lindeman (1926: 8), who stated that adult education should be ‘built around the student's needs and interests’, suggesting that the adult learner should be the centrepiece of the learning environment. Dewey (1929)—arguably the father of experiential learning—emphasised that learning does not occur without reference to context; the two are necessarily interrelated. Knowles et al (2005) noted that learning is enhanced when the adult learner knows why they need to learn something before engaging in the learning process.

In this course, the PBL scenario is built around commonly encountered presentations in paramedicine, helping students see the link between learning and their desired career. Simulation and real-time repercussions enable students to place their learning within the paramedicine context so it is within an authentic learning environment (Lombardi and Oblinger, 2007); it also means they experience the benefits and shortcomings of the decisions they make.

Additionally, the team discussion, the simulation and the debriefing activities each encourage students to draw upon and contribute their own knowledge and previous experiences within the learning environment.

Peer learning, including formative assessment

The PBL tutorial used in this course encourages peer learning and informal peer assessment. For example, students construct a treatment plan that relies upon information provided by their peers who acquired that information in the individual study stage; this activates students as instructional resources for one another within a collaborative setting (Slavin, 1996; Black and Williams, 2009).

The tutorial also enables informal peer learning and formative peer assessment because students observe each other's performance in the oral viva activity and, at other times, quiz one another, especially towards the end of the semester when waiting to undertake the paired or individual oral viva with the lecturer, within a non-judgmental and non-threatening environment. The weekly oral viva (which is not marked) also serves as a type of formative assessment; through this process, students are able to identify their academic progress (Rolfe and McPherson, 1995). Informal peer assessment also occurs in the debriefing activity where individual participants are asked to constructively outline the successes, challenges and mistakes experienced by their team when implementing the treatment plan. It is these formative, interactive situations that influence cognition and ‘internal production by the individual learner’ (Black and Williams, 2009).

Engaging students in the process of self- and peer assessment in this way improves students' retention and practical application of knowledge, as well as helping them to set their own learning goals and work constructively in a collaborative learning environment (Dochy et al, 1999; Hanrahan and Isaacs, 2001).

Lifelong learning, including reflective practice

Self-directed learning activities in the course encourage students to take responsibility for their own learning and develop skills in accessing relevant information (Kaufman, 2003: 213).

Tutorials are structured to lead students to practise reflection in action as well as reflection on action (Schön, 1983). The learner practises reflection in action when participating in the oral viva, and again in the simulation where they are required to draw on their internal capabilities to answer questions and address implementation challenges they had not anticipated. Additionally, learners reflect on action after they have participated in an oral viva. They also reflect on action after they have completed the first simulation and discuss their experiences in the debriefing sessions.

In these ways, lifelong learning and reflection are interwoven into the course and, hopefully, into the student's future paramedic practice. Critical reflection should extend beyond reflecting on performance; it needs to challenge preconceived ideas and experiences to create an environment for truly transformative learning to occur (Mezirow, 1990; Brookfield, 1995). As Lumby (1991: 462) suggests, ‘there is continual transformation occurring as our actions are altered by experience and reflection’.

Benefits and limitations

What are the benefits and limitations of this modified approach to PBL compared to the traditional ‘pure’ approach toward PBL?

Like most PBL models, the modified approach to PBL used within this tutorial still seems to require lecturers to spend more mental energy on preparation than on delivery, and they must still surrender a level of control over the tutorial; the lecturer does not provide answers or share their experiences with students until the last 40 minutes of the tutorial, just before the simulation is repeated.

However, the modified PBL approach helps to address some of the challenges associated with a traditional PBL model. For example, scenario preparation time is reduced through the use of a simple spreadsheet to create scenarios for each week; the lesson is more structured because of clearly articulated tasks within each stage of the tutorial; and the tension between student collaboration and personal technology use is somewhat alleviated by creating designated group discussion and self-study components within the tutorial. These common differences between the traditional and modified approaches to PBL are provided in Table 1.

| Pedagogy | Key characteristics | Educator roles | Participant roles |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional PBL |

|

|

|

| Modified PBL approach |

|

|

|

Adapted from: Bevinakoppa et al, 2016

Abbreviations: PBL–problem-based learning

Conclusion

While progress has been made to transform the design and delivery of this course and results to date have been commendable, further development is likely as the redesign team continues to examine the effectiveness of the approaches used. Not only will further rigorous evaluation of this course occur, but there are also likely to be many novel courses emerging internationally across university-based paramedicine programmes that will warrant further discussion and review.

Success stories need to be shared. It would appear that the modified approach to PBL within this course has been able to ensure delivery of challenging theoretical content (in applied pharmacology) while also promoting the development of non-technical skills such as problem solving, reflective practice and lifelong learning. These educational strategies may be suitable for further consideration.