Introduction

Unstable emergency patients might experience different cardiac arrhythmias. A rarely seen arrhythmia is the p-wave asystole also mentioned ventricular asystole, ventricular standstill or third-degree atrioventricular block with no ventricular escape rhythm. Here, atrial depolarisation is being displayed on the ECG as the only cardiac activity resulting in a patient with no palpable pulses and no consciousness. Left untreated, this arrhythmia will result in cardiac arrest within seconds. Of 2333 patients with non-shockable rhythm cardiac arrest, 6,13% have been described to have p-wave asystole as their initial rhythm (Hulleman et al, 2016). European Guidelines for resuscitation 2015 recommends percussion pacing (PP) as an initial intervention for haemodynamically unstable patients with p-wave asystole or bradyarrhythmias until other means of cardiac pacing are commenced (Soar et al, 2015: 110, 116). The intervention is not scientifically supported and only case reports and reviews of case reports have been published. Our case report contributes to these describing a patient with syncope witnessed by EMS, presenting with p-wave asystole and ventricular standstill, treated successfully with PP and thereof palpable carotid pulses and rise in consciousness.

Case presentation

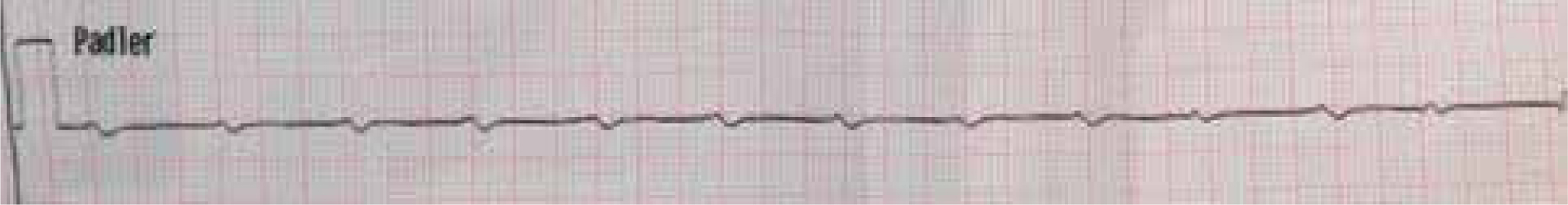

An 87-year-old man collapsed in his private residence in Denmark. EMS was called by the patient's wife and arrived on scene within five minutes. The ambulance mobilised was staffed with one ambulance technician and two paramedics with competencies on Advanced Life Support level and physician backup by telephone. The monitor/defibrillator in use is the LifePak15 (Physio-Control, Redmond, WA, USA). EMS found the patient lying with open eyes on his living room floor, cyanotic, sweating, pale and lethargic. Obtaining previous medical history on scene was not possible, but hospital records afterwards revealed a previous diagnose of bifascicular heart block. Within seconds from initiating the initial assessment, the patient lost consciousness and pulses. Simultaneously, defibrillation electrodes were placed in the anterior/lateral position, and the paddle electrocardiogram (ECG) tracing revealed regular p-waves in a rate around 80 per minute. No ventricular action was noted in the initial 10-second rhythm strip (Figure 1). Chest compressions were commenced briefly, but interrupted as the patient moved his arms and opened his eyes. Once chest compressions stopped, patient again lost consciousness and chest compressions were continued for a few seconds until the patient once again moved. In between both chest compression pauses, the ECG showed regular p-waves with no ventricular action, both paramedics performed pulse check to confirm the ECG tracing. PP was then initiated by one paramedic while transcutaneous pacing was established by another. The paramedic kneeled to the unconscious patient's left side, clenching his left fist and rhythmically tapped the patient's thorax at the left lower part of the sternum in a rate around 80 beats per minute. The intervention resulted in electrical capture in shape of broad QRS complexes on the ECG tracing corresponding with palpable carotid pulses. The patient opened his eyes and moved his upper extremities. The successful PP intervention lasted for 20 seconds until transcutaneous pacing was commenced and further treatment was established. The patient was transported to pacemaker hospital and survived to admission receiving intravenous fentanyl, diazepam, atropine, epinephrine and transcutaneous pacing en route.

Discussion and conclusions

The evidence behind using PP in p-wave asystole is based on case series and case reports. Eich et. al reported in 2007 their three successful cases of PP in two adults and a child. Furthermore, they presented a review of the available literature (Eich et al, 2007). They found three case series (n=160), 13 case reports (n=30) and 4 animal studies (n=24). No studies of higher hierarchic level were identified. The review concluded that PP was found feasible in patients presenting with extreme bradycardia or p-wave asystole with ventricular standstill. In our case report the PP lasted for 20 seconds, but the intervention has been described to be effective for as long as 40 minutes (Wild and Grover, 1970).

Our patient regained consciousness during chest compressions, reflected by movement of his upper extremities and eyes. This was presumably due to the fact that the underlying rhythm actually was third degree atrio-ventricular block with very low ventricular activity though our initial rhythm was interpreted as p-wave asystole. Another explanation to the return of consciousness during chest compressions could be the nature of a witnessed arrest with compressions immediately commenced. Consciousness during manual chest compression has previously been described and it seems that this phenomenon is increasingly observed as focus more frequently is on high-quality cardio-pulmonary resuscitation (Olaussen et al, 2015). Regardless of the underlying rhythm, the patient did have either p-wave asystole or extreme bradycardia, and pacing was indicated.

During our 20 seconds of PP, various signs of return of consciousness was observed. Klumbies et al, who have reported the largest population receiving PP, described consciousness in 69 of their 100 case study subjects undergoing PP (Klumbies et al, 1988). This positive effect of PP corresponds well with the findings of Chan et. al. who in 2002 demonstrated that PP could be as effective as both transthoracic and transvenous pacing. This was reported through a case of a well monitored 55-year-old female with ventricular standstill, receiving PP, transthoracic pacing and transvenous pacing following an asystolic cardiac arrest (Chan et al, 2002).

Our case report indicates that PP is a relevant, feasible and possibly lifesaving measure in one patient presenting with EMS witnessed syncope having p-wave asystole or third degree atrioventricular block with extreme bradycardia as initial rhythm. Our findings correspond well with alike case series and case reports. These reports of PP as a temporary cardiac pacemaker should emphasise that patients having no ventricular activity should be carefully evaluated for the presence of p-waves, as this rhythm might respond initially to PP and subsequently transcutaneous pacing. In a prehospital environment with limited available resources or in the absence of a transcutaneous pacer, PP could be a useful temporary alternative. This case report is to our best knowledge the first presentation of Danish paramedics intervening with PP.