In cardiac arrest, the primary interventions used to regain spontaneous circulation are cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), defibrillation and pharmacological agents such as adrenaline. Recent years have seen a greater emphasis on high-performance CPR, which is likely to be responsible for the increasing rate of CPR-induced consciousness (CPR-IC) (Pound et al, 2017). CPR-IC is a poorly understood phenomenon where patients regain consciousness and pain perception during CPR without return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) (Pourmand et al, 2019).

Although CPR-IC has been discussed in the literature for upwards of 30 years, an agreed definition of it does not exist (Carty and Bury, 2022). In pulseless patients undergoing CPR, CPR-IC has been described as one or more of spontaneous speech, body movement, recovery of jaw tone or eye-opening, which lapse on cessation of CPR (Olaussen et al, 2015).

A retrospective observational study by Olaussen et al (2017) demonstrated that in 16 558 cases of EMS attempted resuscitations, there were 112 (0.7%) instances of CPR-IC, which increased in frequency from 0.3% in 2008 to 0.9% in 2014 (P=0.004). Incidence is expected to climb because of the rising use of automatic external defibrillators, mechanical CPR devices such as the Lund University Cardiopulmonary Assist System, and crowdsourced responder networks such as GoodSAM, making this scoping review timely and relevant.

Complications of CPR-IC

CPR-IC has proven problematic to practitioners attending out-of-hospital cardiac arrests (OHCAs) as patients hinder resuscitative efforts through a range of actions. Patients have withdrawn from compressions, removed airway devices, presented with combativeness and agitation, and physically obstructed rescuers by pushing or grabbing at them (Doan et al, 2020). There have also been reports of patients biting down on oropharyngeal airway devices and moving their heads away from bag-valve masks being used to ventilate. These have resulted in more frequent pulse checks being needed, as well as delays and interruptions to compressions.

In addition to clinical implications, rescuers have described feeling distressed and uncomfortable when trying to resuscitate an awakening patient (Gregory et al, 2021). CPR-IC may also affect the patient’s experience of resuscitation. One study described a man in cardiac arrest who was able to accurately recall events that took place while he was being resuscitated during approximately three minutes of CPR-IC (Parnia et al, 2014). This naturally raises questions about pain and psychological trauma.

Management of CPR-IC

At present, no consensus guidelines exist on the best way to manage pain or increasing consciousness in CPR-IC. Current strategies differ greatly but include: physical restraint; medications such as benzodiazepines, opiates and paralytics; and analgesics such as ketamine (Olaussen et al, 2015; 2017). Use of these medications can lead to complications such as altered neurological findings, respiratory depression and haemodynamic instability.

This is relevant both when deciding whether to continue resuscitation efforts (Bihari and Rajajee, 2008) and in ROSC, where hypotension is associated with increased mortality (King et al, 2021). One study found the use of sedatives or analgesia correlated with greater cessation of resuscitation at the scene, prolonged time to ROSC and lower survival to hospital admission (Olaussen et al, 2015). This could be because of impaired vasomotor tone and subsequent decrease in coronary perfusion pressure caused by these medications (Olaussen et al, 2017). Ketamine can also lead to complications such as increases in myocardial oxygen consumption and cerebral oxygen demand. This raises questions about poorer neurological outcomes (Rice et al, 2016).

Moreover, the complexities of intra-arrest physiology, including varying cerebral perfusion pressure, make estimating effective drug doses and overall effects difficult. This is further complicated by CPR-IC drugs being used in parallel with the current standard-of-care advanced life support medications. Examples include the compounding effects of ketamine and adrenaline, and the opposing effects of fentanyl and adrenaline. Practitioners mostly witness CPR-IC in public places, making guidelines particularly important for out-of-hospital responders (Doan et al, 2020).

Rationale for review method

Scoping review methodology will be used to describe and map the subject of CPR-IC. Scoping reviews are considered a legitimate and rigorous methodology to collate and describe existing literature and identify knowledge gaps in an area (Munn et al, 2018). They are well suited to topics where insufficient literature is expected (Peters et al, 2022). CPR-IC management is an emerging, poorly understood subject, so lends itself to a scoping review.

This review will be undertaken following the latest JBI methodology (Peters et al, 2020). This protocol has been produced following the bestpractice guideline for ScR protocols (Peters et al, 2022). The review report will adhere to the PRISMA-ScR reporting guideline (Tricco et al, 2018).

A preliminary search of MEDLINE via Ovid revealed two relevant scoping reviews on CPR-IC. The first study used a database-only search and included cases in any setting, but was limited to adults and specifically the management of preventing consciousness (West et al, 2022). The second reviewed only prehospital guidelines for CPR-IC (Howard et al, 2022). The present scoping review will cover all aspects relating to the care of out-of-hospital CPR-IC and will encompass a broader search strategy and eligibility criteria.

A preliminary literature search found case reports and other publications reporting on aspects of the care of the patient with CPR-IC, which are likely to be included in the scoping review report (Lewinter et al, 1989; Bihari and Rajajee, 2008; Doan et al, 2020; Gregory et al, 2021).

Consultation with key stakeholders is recommended when conducting a scoping review (Pollock et al, 2018). Therefore stakeholders, including clinicians who provide care in the out-of-hospital setting and who are involved in the development of clinical practice guidelines through the reviewers’ professional networks have been and will continue to be consulted throughout this review process.

The protocol for this scoping review was registered prospectively with the Open Science Framework on 25 August 2022 (https://osf.io/zmgcx/).

Aims

This scoping review aims to systematically map the available literature relating to the management of CPR-IC in the out-of-hospital environment and to identify any gaps in knowledge that may require further research. The review question is: what is the current scope of knowledge regarding all aspects of care of CPR-IC in OHCA globally?

Methods

Eligibility criteria

Population

Sources about the care of human patients of any age, sex, ethnicity, pregnancy status or comorbidities who experience CPR-IC during resuscitation for cardiac arrest will be included.

Concept and context

The overall concept and context of this scoping review are intricately linked, as the concept of CPR-IC cannot occur outside the context of cardiac arrest. The concept and context have therefore been combined.

This scoping review will include literature that reports on any aspect of the care of CPR-IC in OHCA resulting from any cause (i.e. medical or trauma). This may include but is not limited to triggers and identification of CPR-IC, clinical decision-making, reassurance, physical restraint or of medication administration.

The specific context of this scoping review is the out-of-hospital setting. Other commonly used terms to describe this context include emergency medical services, ambulance services or paramedic services. This review will comprise sources relating to out-of-hospital clinicians including but not limited to paramedics, nurses, medical practitioners and the various levels of ambulance technicians (e.g. first responders, emergency medical technicians or ambulance officers) managing patients in the out-of-hospital setting.

Literature reporting on in-hospital care, including emergency department and intensive care, will not be included in this scoping review.

Types of evidence sources

Because of the limited literature available on the present topic, all types of evidence sources, text and opinion literature will be included. If deemed relevant to the review question, unpublished (grey) literature will also be considered. While recognised as a limitation, only sources published in English will be included owing to resource limitations.

Information sources

The databases to be searched from inception include Web of Science, MEDLINE (Ovid Interface), CINAHL Complete (EBSCO), Scopus and Embase. For completeness, a search of Google Scholar will also be undertaken (Haddaway et al, 2015; Bramer et al, 2017). The Google Scholar search results will be limited to the first 200 as recommended by Haddaway et al (2015), ordered by relevance and completed on an incognito browser to reduce bias.

Grey literature will be included in this scoping review to avoid publication bias and to ensure a thorough review of the available literature (Aromataris and Pearson, 2014). The advanced search function on Google will be used to conduct this search. A new browser will be installed to avoid personalisation of results. These will also be limited to the first 200, ordered by relevance. A search for theses will be conducted in ProQuest Dissertations and Theses and EBSCO Open Dissertations.

Clinical trial registries will also be included to identify both completed and ongoing clinical studies (Baudard et al, 2017). These will be retrieved from ClinicalTrials.gov, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform and the International Traditional Medicine Clinical Trial Registry.

The websites of national and international resuscitation organisations and developers of evidence-based clinical guidelines such as the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation, Australian Resuscitation Council, European Resuscitation Council, Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence and American Heart Association will be searched and the full details including URLs of each web page cited will be listed in the final report. The UK database, amber, the home of ambulance services research, will also be searched.

Because literature in the area is limited, the reference lists of publicly available clinical practice guidelines of the public ambulance services of Australia, New Zealand, Ireland and the UK will be reviewed for possible sources. The guidelines searched will be listed in the final review report. The correspondence authors of sources included will be contacted and the reference lists scanned for further sources.

A limitation of electronic database searches is that they may not reveal all possible literature on a topic (Armstrong et al, 2005). To ensure that the maximal possible literature will be included in the review, an electronic hand search will be undertaken in peer-reviewed journals of high relevance to out-of-hospital care (Appendix 1). This search will be limited to the past 10 years because of practical time constraints.

Search strategy

To ensure optimal quality of the search strategy, a research librarian with expertise in systematic literature searching has been involved with the review since inception (Rethlefsen et al, 2015). A peer review of the search strategy following the PRESS recommendations will also be undertaken (McGowan et al, 2016). A full draft search strategy for the MEDLINE database is shown in Table 1. It is recognised that in scoping reviews, searching the literature is an iterative process, so this draft strategy may be modified as more search terms may need to be added. Any modifications will be identified in the review report.

| # | Searches |

|---|---|

| 1 | Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation/or Heart Massage/ |

| 2 | Consciousness/or Awareness/ |

| 3 | 1 and 2 |

| 4 | ((resuscitat* or CPR or chest compress* or chest-compress* or heart-massage or heart massage or CPA or cardi* arrest*) adj5 (aware* or conscious* or movement* or wakeful* or awake*)).tw,kf. |

| 5 | (CPR-IC or CPRIC).tw,kf. |

| 6 | 3 or 4 or 5 |

| 7 | exp animals/not humans.sh. |

| 8 | 6 not 7 |

Searches will be restricted by publication date starting from 1989 as this is when reports of CPR-IC first appeared in the literature (Lewinter et al, 1989).

Study records

Records management

Covidence software will be used for screening. Search results will be uploaded, and data from included sources will be extracted using a data charting table developed in MS Excel version 2206.

Selection

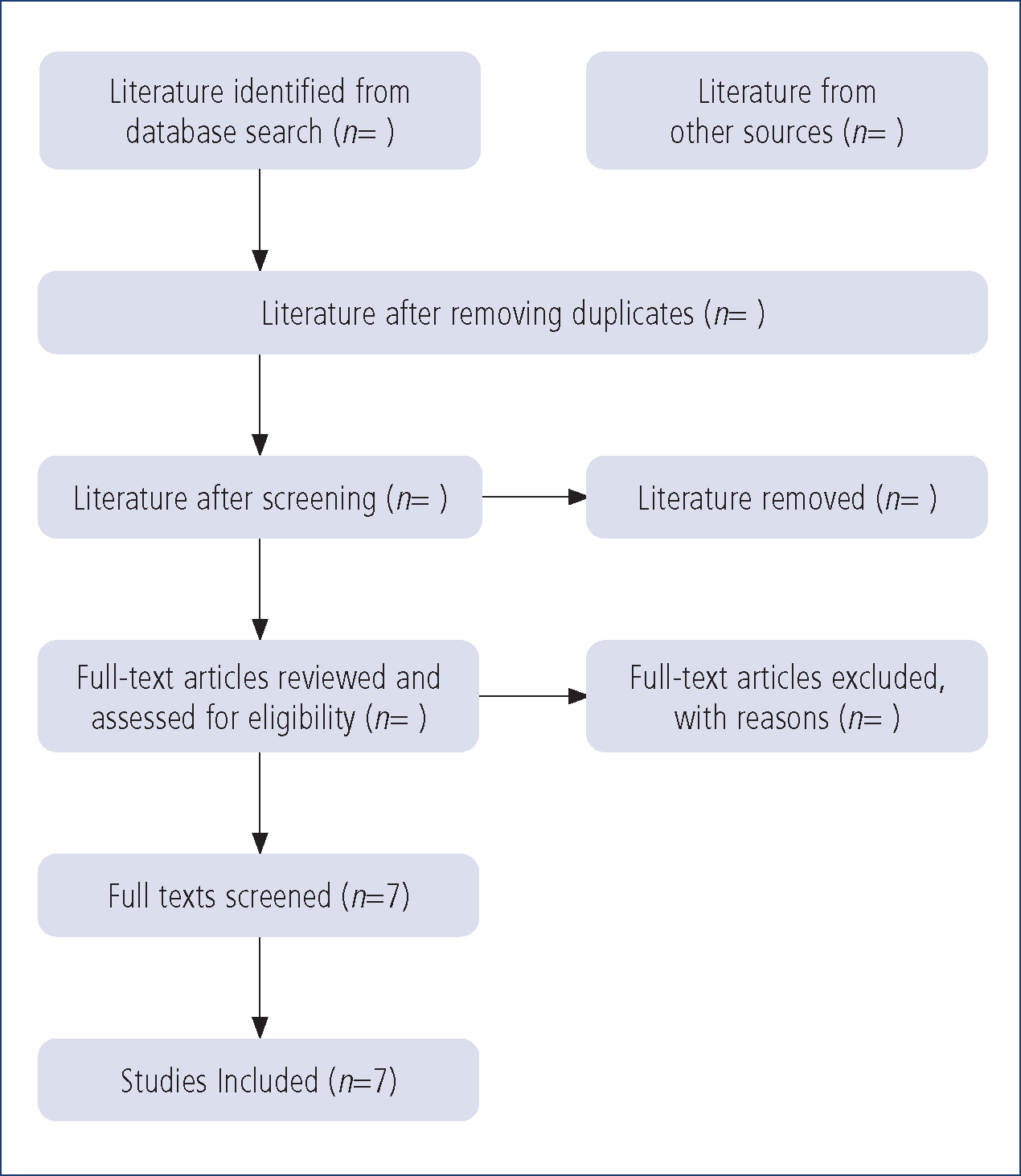

After the search, all identified citations will be collated and duplicates removed. Two reviewers will independently screen titles and abstracts to determine whether they meet inclusion criteria.

Next, the full text of selected citations will be assessed in detail against the inclusion criteria by the two independent reviewers. The reasons for excluding sources of evidence at full text that do not meet the inclusion criteria will be recorded and reported in the scoping review report.

Any conflicts that arise between reviewers at each stage of the selection process will be resolved through discussion with the broader review group. The results of the search and the study inclusion process will be reported in full in the final scoping review.

Data charting

A draft data extraction tool developed by the reviewers will be used to extract data from the included sources (Table 2). A subset of relevant sources will be used to pilot the table.

| Source | Year of publication | Authors | Study design | Country | Number of patients | CPR-IC presentation | CPR-IC management | Outcomes | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Because of the iterative nature of scoping reviews, further refinements may be necessary. Should any updating or refinement occur, this will be noted in the scoping review report. One reviewer will extract the data and the results of each source will be verified by a second reviewer.

In adherence to guidance for scoping reviews, a formal quality appraisal of the included literature will not be completed (Peters et al, 2022).

Data items

Data items related to eligibility criteria will be extracted, as well as relevant data such as country of origin of the source, type of evidence/study, year of publication and key findings relevant to the question, ‘What is the current scope of knowledge regarding the management of CPR-IC in OHCA globally?’

Presentation of results

The screening process will be reported per the PRISMA-ScR recommended flow diagram (Figure 1) (Tricco et al, 2018).

This scoping review will present the data and the results in narrative and tabular form. Narrative descriptions will focus on the key concepts and themes in the included sources.

The review group may also present further diagrammatic representation of the results following consideration of the data.

Summary

The incidence of CPR-IC is expected to continue to rise. The associated complications range from impaired resuscitation efforts to psychological distress, and no consensus guidelines currently exist. Given that CPR-IC is most often observed in the out-of-hospital environment, it is most significant for first responders.

This protocol provides the framework for the first scoping review which will cover all aspects relating to the care of out-of-hospital CPR-IC using a broad search strategy including grey literature. It will outline the extent of knowledge and identify areas requiring more research in the out-of-hospital care of the patient with CPR-IC.