Trauma is a major public health issue and accounts for a significant portion of global morbidity and mortality. Worldwide, injury causes a death every 6 seconds (World Health Organization, 2014). Approximately 9% of the world's population dies because of injury, with more than five million deaths from injury recorded annually, 1.2 million of these in young people. In the United States, injury was the fourth leading cause of death in 2015 and, by 2017, was ranked third (Heron, 2017). In the UK, trauma is the leading cause of death in people aged ≤49 years (Office for National Statistics, 2018).

Fortunately, improvements in the components of the care system for trauma patients, including trauma prevention, out-of-hospital care and acute and post-trauma care, have reduced mortality and morbidity in patients with trauma injuries (Celso et al, 2006). However, there are concerns that trauma education is not improving as rapidly as other components in care system (Jayaraman and Sethi, 2010; Jayaraman et al, 2014).

Emergency medical service (EMS) personnel provide out-of-hospital care for trauma patients and can reduce mortality and morbidity (Ornato et al, 1985; Sullivent et al, 2011). In developed countries, the establishment of an appropriate EMS can prevent 25% of deaths that would have resulted from trauma (West et al, 1979; Cales, 1984; Cales and Trunkey, 1985). The South Korean government reached its goal to reduce trauma mortality to 20% by 2020 by establishing an effective trauma management system and building 17 trauma centres in the country (Jung et al, 2016; 2021).

A growing body of literature indicates that survival rates improve when EMS personnel undertake trauma training such as prehospital trauma life support (PHTLS), advanced trauma life support (ATLS) and advanced life support courses (Jacobs et al, 1984; Cayten et al, 1993; Liberman et al, 2000; Johansson et al, 2012). However, some studies have found EMS personnel may have low confidence in their technical and non-technical trauma skills despite undertaking such courses (Woods, 2006; Hjortdahl et al, 2009; Garden et al, 2015).

Exposure to injured patients often leads to anxiety, stress and depression in EMS staff (Bentley et al, 2013). Similarly, paramedics respond to a high rate of patients injured in an act of violence, which can lead to discomfort and anxiety when delivering care. Paramedics who are less exposed to risks and life-threatening conditions are more confident in their skills (Regehr, 2006).

Examining the efficacy of trauma training programmes for health professionals can be useful in improving trauma care. In the literature, confidence has been defined as ‘the belief in oneself, in one's judgment and psychomotor skills, and in one's possession of the knowledge and ability to think and draw conclusions’ (Etheridge, 2007). However, the term self-efficacy has been expressed by scholars such as Bandura, who stated that the terms self-efficacy and self-confidence can be used interchangeably (Bandura, 1977; 1997; Papaioannou and Hackfort, 2014). The term ‘confidence’ is used in this paper.

This scoping review aimed to review the literature about trauma educational courses for health professionals to determine the impact of such courses on a their confidence.

The authors use the term ‘healthcare providers’ as it includes a broad range of health professionals, such as paramedics, physicians and nurses, who are all part of the EMS team.

Method

The scoping review framework was based on the guidelines of Arksey and O'Malley (2005), which are intended to address broader topics and different study designs. Furthermore, Cooper et al's (2021) recently developed scoping review checklist was also used to ensure the review would be comprehensive.

The scoping review had six stages:

Stage 1: identifying the research question

This scoping review aimed to determine the impact of trauma training or education on practitioner confidence. The research question was: ‘Does trauma training improve healthcare providers' confidence?’

A population, concept and context (PCC) framework was used to determine the review question and identify keywords and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms (Munn et al, 2018) (Table 1).

| PCC | Term | Keywords | MeSH |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population | Healthcare providers | Paramedics, emergency medical technicians, physicians, nurses, emergency medical services | Ambulances/emergency medical technicians/air ambulances/paramedic*.tw./ems.tw. |

| Concept | Trauma education | Trauma, injury, wounds, advanced trauma life support, prehospital trauma life support, international trauma life support, primary trauma care | Emergency service, hospital, wounds and injuries/education, medical, continuing traumatology |

| Context | Confidence | Confidence, self-confidence, self-efficacy, efficacy | confiden*.tw./self-confidance.tw./self-efficacy.tw./efficacy.tw. |

Abbreviations: PCC–Population, concept and context; MeSH–Medical Subject Headings.

Source: Munn et al (2018).

Stage 2: identifying relevant studies

The search was carried out on 7 August 2021. The authors considered published and unpublished studies in the following databases: Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid Embase, Ovid Emcare, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Scopus, Google Scholar and Trove.

The reference lists of the included studies were also reviewed for additional potential studies. Articles from these lists were selected based on their abstract. In addition, experts in the field of trauma were consulted. A combination of terms was used in searching using the PCC framework (Munn et al, 2018) (Table 1).

Stage 3: study selection

Inclusion criteria

Studies that assessed the impact of trauma training courses on the confidence of healthcare providers (out of and in hospital) were included. Trauma training in this review included any short courses attended by practitioners, including paramedics, physicians and nurses.

Exclusion criteria

Studies that examined non-trauma training or training with non-healthcare providers were excluded. Articles in languages other than English were not included. Moreover, studies about non-trauma courses were excluded, including a mass casualty incident, as the focus was on on-scene management and evacuation plans rather than practitioners' skills in managing injured patients.

Screening process

EndNote X7 (Clarivate Analytics, US) was used to upload studies and potential duplicates were removed. Two independent reviewers screened the titles and abstracts for inclusion, and potential studies were downloaded for a full-text review.

Studies that met the inclusion criteria were included in the final analysis. In addition, the reference lists of the included studies were examined for potential studies, as mentioned above.

Search results

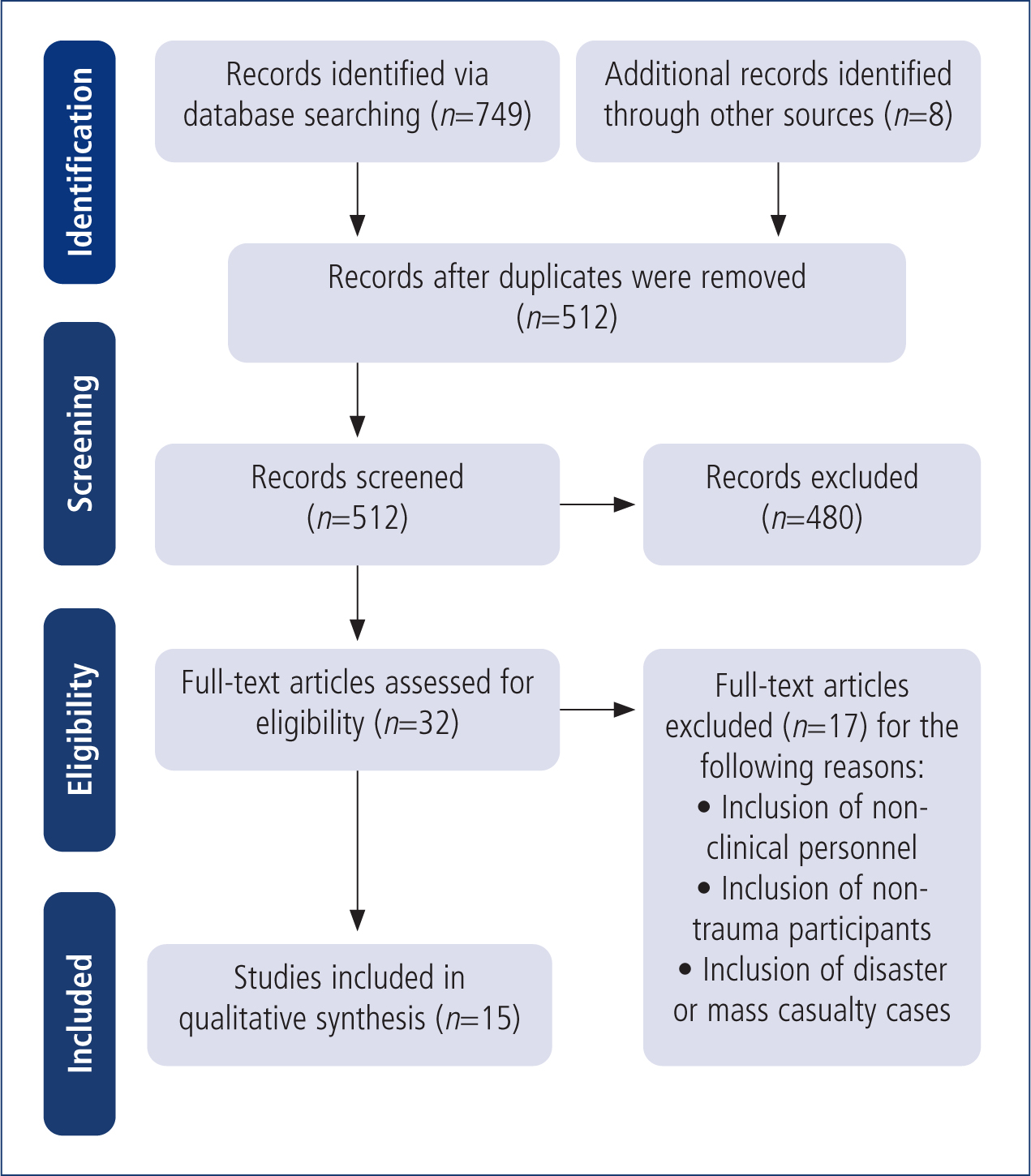

A total of 749 articles were retrieved from the search and an additional eight articles were captured through a hand search of grey literature. Out of 749 studies, 245 were duplicates, leaving a total of 512 articles eligible for title and abstract screening. A total of 480 irrelevant articles were removed after screening, leaving 32 for full-text review. Seventeen articles were not eligible for inclusion; leaving 15 articles for the scoping review (Figure 1) (Tricco et al, 2018).

Stage 4: charting data

Table 2 provides details of the studies included in this review, as recommended by Arksey and O'Malley's (2005) method. Data include: year of publication, author details, country of publication, study type, sample size, key findings and themes.

| Year | Author | Country | Type of study | Participant role, sample size | Key findings | Themes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1991 | Porter | US | Cross-sectional, prospective study | Paramedics, n=111 |

|

Knowledge |

| 1998 | Ali et al | Trinidad and Tobago | Quantitative study | Paramedic personnel, n=28 |

|

Knowledge |

| 2002 | Schreiber MA et al | US | Quantitative study using before and after questionnaires | Military care providers, n=20 |

|

Experience |

| 2005 | Barsuk et al | Israel | Prospective controlled study | Post-internship physicians, n=72 |

|

Knowledge |

| 2008 | Wisborg et al | Norway | Quantitative study | Physicians and nurses, n=4203 |

|

Knowledge and experience |

| 2009 | Rubiano et al | Colombia | Quantitative study | Combat nursing students, n=374 |

|

Knowledge |

| 2011 | Breederveld et al | The Netherlands | Quantitative study | Medical staff in hospital emergency departments and ambulance services, n=208 |

|

Knowledge |

| 2013 | Pemberton J et al | Guyana | Mixed methods (multiple-choice questions, checklist and TTAT) 0.1.4 | 20 physicians, 17 nurses, and 10 paramedics n=47 |

|

Experience |

| 2017 | Abelsson et al | Sweden | Clinical trial (intervention study) | Nurses in prehospital emergency care n=63 |

|

Experience |

| 2017 | Häske et al | Germany | Mixed methods | Paramedics and physicians n=312 |

|

Experience |

| 2017 | Ologunde et al | South Africa | Qualitative study | Frontline healthcare workers n=321 |

|

Experience |

| 2018 | Mills et al | Australia | Pilot study | Undergraduate paramedicine students n=50 |

|

Experience |

| 2018 | Lam et al | Vietnam | Quantitative study | Nurses n=353 |

|

Knowledge and experience |

| 2019 | Falaki et al | Iran | Quantitative study (pre and post test) | Emergency medical services staff n=144 |

|

Knowledge |

| 2020 | Dehghannezhad et al | Iran | Quantitative study | Prehospital emergency personnel n=120 |

|

Knowledge and experience |

Abbreviations: TTAT–Trauma Team Assessment Tool

Stage 5: collating, summarising and reporting results

The 15 studies included in this review comprised the following study designs: quantitative (n=9); qualitative (n=1); mixed methods (n=2); prospective controlled (n=1); pilot (n=1); and cross-sectional and prospective (n=1). These studies were based in the following countries: US and Iran (n=2); Trinidad and Tobago (n=1); Israel (n=1); Norway (n=1); Vietnam (n=1); South Africa (n=1); Colombia (n=1); the Netherlands (n=1); Canada (n=1); Sweden (n=1); Germany (n=1); and Australia (n=1).

The studies covered different courses. The short courses were: PHTLS (n=4); ATLS (n=2); emergency management of severe burns (EMSB) (n=3); trauma team training (n=1); modified ATLS courses (n=1); and scenarios and training in specialised hospitals (n=4).

These courses can impart the ABCDE approach for injured patients based on the ATLS guidelines. Some courses were modified to achieve the trauma care needs of their facilities, and some focused on improving the skills of cooperation, communication and leadership. Furthermore, some courses were one-day sessions with a combination of theory and skills to develop an understanding of prioritising, providing leadership knowledge, accepting changes and communication (Wisborg and Brattebø, 2008).

Some courses were provided to physicians, nurses and paramedics who needed to improve their skills in performing procedures such as cardiopulmonary resuscitation, recovery position placement, patient log roll, venous cutdown, endotracheal intubation, cricothyrotomy and chest tube insertion (Pemberton et al, 2013). Other courses focused on burns and covered how to recognise, assess, stabilise and transfer patients to burn centres, and included EMSB.

Stage 6: consultation

Two experts who had published works on trauma education were consulted via email for any additional recommendations or suggestions regarding the final articles. Both agreed with the list of the 15 articles and did not suggest other studies that could be included.

Discussion

Healthcare providers' confidence has been associated with having a professional role and being a competent practitioner (Holland et al, 2012). Confidence has been recognised as a desirable characteristic of healthcare providers and is considered an important facet of competence (Cohen and Cohen, 1990; Ytterberg et al, 1998). However, studies examining paramedic confidence are limited.

Confidence is a sophisticated concept because it involves a combination of personal beliefs and achievements. For example, the psychosocial theory gives four factors in the development of confidence—experience, efforts, information (knowledge) and decision-making (Paese and Sniezek, 1991).

Numerous training courses could help achieve and maintain good performance in clinical settings and positive patient outcomes (Wisborg and Brattebø, 2008).

Confidence was assessed through different approaches in the 15 studies identified in this scoping review. These studies examined the major themes of confidence and found two main subthemes—knowledge and experience—which underpin the concept of confidence.

Knowledge

Of the 15 studies, six evaluated the knowledge of participants, which is the main factor affecting confidence. Eight studies evaluated participants' level of knowledge before and after the training courses. Overall, the results showed differences in knowledge before and after training.

The efficacy of five training courses was described as the ability to improve participants' performance based on tests and skills evaluation before and after the course. Knowledge was evaluated using multiple-choice questions, and the difference in knowledge after these training courses was significant.

For example, a study in Colombia showed significant improvement in the knowledge of 374 combat nurses (from a 59.8% score before the course to 98.8% after; p<0.01) (Rubiano et al, 2009). Moreover, 4203 practitioners self-reported that their confidence and knowledge level improved after participating in a combat tactical medicine course (Wisborg et al, 2008; Lam et al, 2018; Falaki et al, 2019; Dehghannezhad et al, 2020).

Changes in knowledge were investigated in three studies using a checklist evaluation where the results showed participants' skills improved after training (Ali et al, 1998; Barsuk et al, 2005; Rubiano et al, 2009). In the Netherlands, a study about the value of EMSB courses for emergency care practitioners showed the need for this and additional training in nearly one-third (34%) of the participants. Participants who had not been trained overestimated the total body surface area, and 87% of them used an incorrect formula for fluid resuscitation (Breederveld et al, 2011). In addition, the efficacy of training in the clinical care of actual combat casualties is not known (Rubiano et al, 2009).

Knowledge retention was evaluated in three studies, and all showed that participants' knowledge retention decreased over time.

A cross-sectional study conducted in the United States evaluated 111 paramedics' attitudes and knowledge regarding three teaching methods—lectures, video and computer-assisted instruction (CAI). After 60 days, knowledge retention had decreased after use of all three teaching methods. However, CAI led to better knowledge acquisition compared with the other methods (Porter, 1991).

Knowledge and skills can deteriorate if they are not used or updated regularly (Broomfield, 1996) and applying knowledge in practice improves retention.

Experience

Five studies showed associations between participant experience, confidence and knowledge.

In Norway, a study was conducted to evaluate the impact of a 1-day course on trauma team performance, knowledge and confidence over 8 years in 4203 physicians and nurses. The self-reported data showed a significant improvement in the participants' confidence. However, there were significant differences in trauma care regarding patient outcomes between hospital levels.

A negative association between experience and knowledge was reported in a systematic review where physicians with more experience were more likely to provide low-quality care (Broomfield, 1996; Choudhry et al, 2005; Ologunde et al, 2017).

Moreover, a study was conducted to assess the efficacy of a training mission for 20 military care providers who engaged in a 1-month training course in a level I trauma centre in a civilian hospital. A change in environment can provide exposure to different cases and improve the confidence of healthcare providers. This study, in the US, found that the 20 military care showed significant improvements in confidence (p<0.005) after spending 1 month in the trauma centre (Schreiber et al, 2002).

Some studies assessed associations between the frequency of scenarios or simulation and the efficacy of training. However, there was no conclusive evidence of the effect of simulation on trauma care. However, one study examined the association between the frequency of simulation and trauma care skills in 63 nurses. Results showed significantly greater improvement in knowledge and skills management in participants who attended four scenario stations than in those who attended two scenario stations (Abelsson et al, 2017). Therefore, the repetition of simulation contributes to improvement at an individual level. However, whether this individual improvement via simulation experience transfers to the trauma care setting remains unknown (Laschinger et al, 2008).

Limitations

The scoping review has several limitations. First, there were limitations in the search strategy conducted by one of the authors and an independent librarian specialist because of the small number of MeSH terms; as a result, some studies might not have been retrieved. A higher number of keywords should be used to overcome this. The authors attempted to address this by consulting experts for additional recommendations.

Second, some studies focused on subjective evaluation and not the actual competence of trauma care. Self-assessment is not a reliable tool for measuring the quality of clinical care, and an inverse relationship between external assessment and self-assessment has been observed (Davis et al, 2006).

Finally, it can be argued that evidence about the impact of training on the confidence of healthcare providers is inadequate. However, the authors believe that the studies included provided enough evidence about the limited ability of participants to self-assess their confidence.

Conclusion

Healthcare providers have reported that their confidence improves after attending trauma courses. In addition, their knowledge improves after training, as multiple-choice question results show.

However, the literature shows knowledge is retained for 4 months and that the CAI method of teaching was the most effective. An inverse association was observed between experience and knowledge, and self-assessment by participants showed significant improvements. Therefore, trauma training has a significant effect on practitioner knowledge.

Furthermore, frequent training has a positive impact on healthcare providers' knowledge. Therefore, more studies about this area, particularly for paramedics, should be conducted to evaluate continuing education and confidence. The authors suggest studies that focus on paramedics' confidence in dealing with trauma cases that might cause anxiety.