Since the COVID-19 pandemic was declared by the World Health Organization (2020) on 11 March 2020, healthcare systems, practitioners and communities have experienced momentous change and strain.

While paramedicine is a relatively new profession, paramedics have become an essential component in the healthcare system for the public emergency response (Bigham et al, 2013).

However, studies have largely focused on the views of physicians, nurses and hospital administrators, rather than paramedic practitioners (Alwidyan et al, 2020). With existing literature in paramedicine solely addressing logistical planning, workforce availability, triage ethics and vaccination considerations, there was limited evidence surrounding the Canadian operational environment and paramedic services' capacity to develop and implement evidence-informed programmes while responding to a pandemic (Cavanagh et al, 2020).

Literature pertaining to paramedicine has emerged since the start of the pandemic related to intubation, handover at hospital and amendments to the scope of practice and practice recommendations in the context of COVID-19 (Boehringer et al, 2020; Buick et al, 2020; Nolan et al, 2020; Feldman et al, 2021).

Other paramedicine-related literature has addressed the impacts of training on different aspects of pandemic preparedness, paramedics delivering bad news during COVID-19, effects of COVID-19 on paramedic student education, impacts on paramedic call volume and patient acuity, and approaches to leadership in paramedicine in a variety of international contexts (Suppan et al, 2020; Boechler et al, 2021; Campbell, 2021; Ferron et al, 2021; Williams et al, 2021; Yadav et al, 2021).

One area of literature lacking attention is the day-to-day lived experiences of paramedics throughout the COVID-19 pandemic and the meaning that their experiences hold for them. Thus, the purpose of this paper is to explore the insights provided by paramedics about their daily experiences and the ways in which COVID-19 impacted them both professionally and personally early in the outbreak.

Methods

This research study focused on gaining a better understanding of the lived experiences of paramedics throughout the initial stages of the COVID-19 outbreak.

The conception of this study was informed by a phenomenological study that examined the experiences and the roles of nurses across Saskatchewan in the early stages of the pandemic (Nelson et al, 2020; 2021).

However, it was not feasible to employ a phenomenology methodological approach for this study because of limited research resources paired with a sense of urgency to capture paramedic sentiments and experiences early in the outbreak.

As such, this study is a descriptive qualitative study that aimed to provide a comprehensive description of a particular phenomenon, its characteristics and an understanding of the everyday events (Colorafi and Evans, 2016), namely the lived experiences of paramedics during the initial stages of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In an effort to maintain phenomenological overtones within this study, researchers adapted and expanded the interview questions from the study mentioned above (Nelson et al, 2021) to guide the survey development.

Study design

Paramedics from across Canada were invited to participate in an online survey on demographics, work and role description, call volumes before and after the pandemic broke out, perceptions of personal health and safety risks related to COVID-19 exposure, and open-ended questions asking about the changes experienced as a paramedic since the onset/outbreak of COVID-19 in Canada.

The survey was developed by a team of paramedic researchers from three provinces with operational experience in five distinct operational environments to ensure it applied across provinces. The SurveyMonkey platform was used. The open-ended questions posed to the respondents are shown in Box 1.

Participants

Participants were recruited from paramedic services across Canada through a poster on social media cascaded to paramedic services, unions, licensing bodies and paramedic associations.

The survey was open to paramedics who were licensed/certified at primary, advanced and critical care levels and actively practising in Canada.

Procedures

All data were read through at least once before being coded.

Quantitative responses were analysed using SPSS (version 27) to provide descriptive and cross-tabulations of risk perception with age, gender, location, years of experience and designation.

Qualitative responses were divided into provincial groupings and each grouping was assigned to two paramedic research team members for independent analysis using NVivo (version 12). The process of determining and analysing themes was inductive, iterative and recurring, and continued until the point of saturation (Braun and Clarke, 2006).

Process of reflexivity

The research team members working on this study all have a certain understanding of the nature of paramedic work, some working as practitioners during the COVID-19 pandemic.

As such, to maintain an emphasis on openness and to question their previous understanding of phenomena, continuous reflection and discussion occurred within the research team, challenging their experiences within and outside their own diverse geographical jurisdictions and experiences.

To further mitigate the potential of preconceptions and biases unintentionally held by researchers tainting the validity of findings, a subsequent analysis was contracted through the University of Saskatchewan's research and consulting service, the Canadian Hub for Applied and Social Research, which resulted in consistent findings across both analyses.

Ethics

Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Saskatchewan, York University and the Humber Institute of Technology and Advanced Learning research ethics boards.

Results

Demographics

A total of 424 respondents completed the survey between April and August 2020.

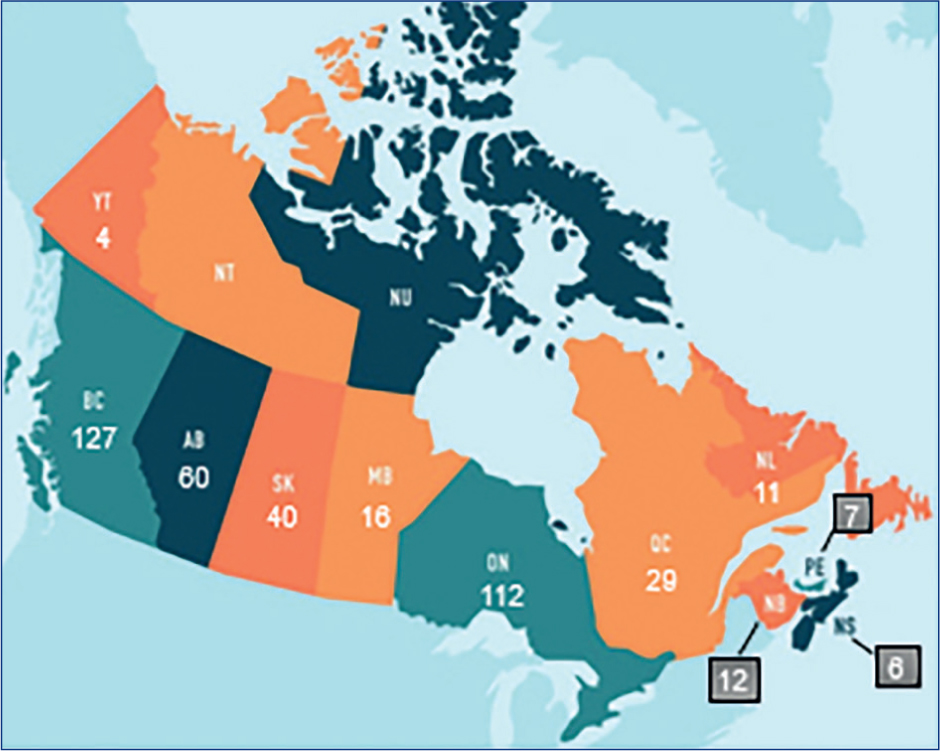

Representation from 10 provinces and one territory was obtained with the highest representation being from British Columbia (n=127) and Ontario (n=112) (Figure 1).

More than half (58.3%) of the respondents identified as men and 41% of respondents identified as women. A very small proportion (<1%) identified as non-binary or preferred not to answer.

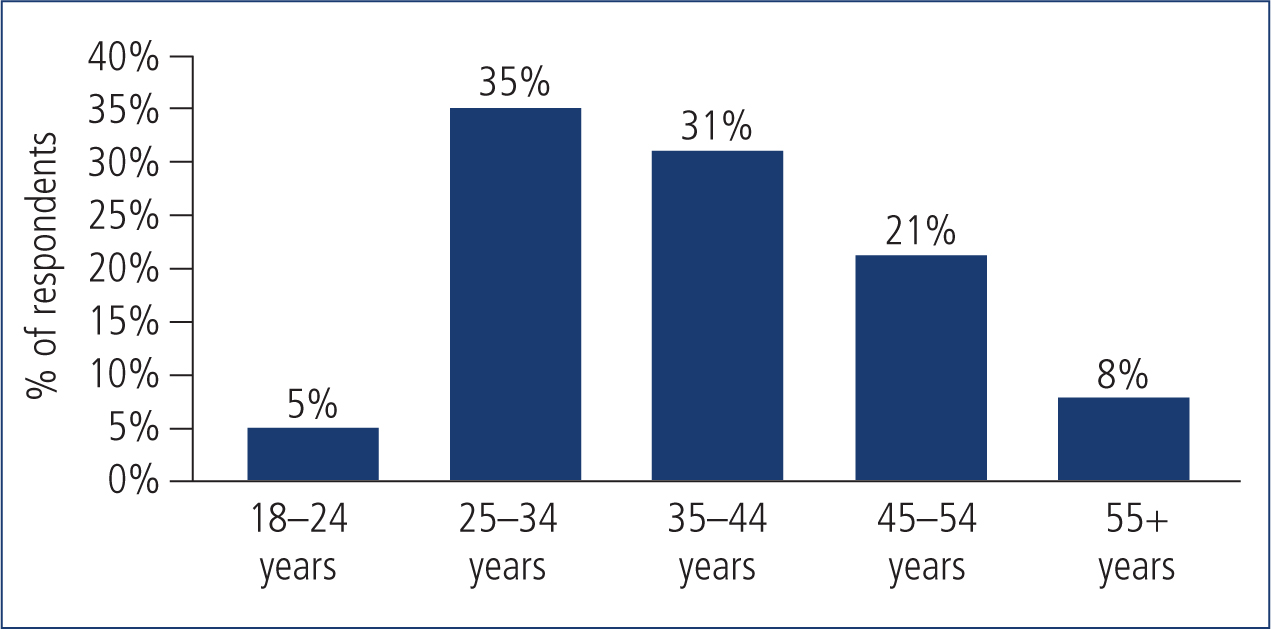

The distribution of respondent age range is shown in Figure 2.

Role and experience

Respondents were asked to identify the number of years they had worked as a paramedic, the work environment(s) in which they practised and their designation.

The sample was fairly experienced, with 57% reporting ≥10 years of experience. Nearly all respondents were working in an ambulance setting (n=396), with 93 respondents working in at least two settings, usually ambulance in combination with another setting.

The most commonly selected designation was primary care paramedic (PCP) (64%), but 43 respondents had some overlapping designations. For example, 12 respondents with a PCP designation also held a community paramedic designation, and nine others with a PCP designation also held an ‘other’ designation. Among those with an advanced care paramedic designation, 14 also held a community paramedic designation.

Perception of risk

Respondents were asked if they felt that their health and safety were more at risk since the COVID-19 outbreak. Very few felt that their risk did not increase, and most felt that there was greater risk in their work, some quite significantly. No correlation was found between regional active COVID-19 cases and heightened risk perception.

Themes identified

Paramedics identified significant changes in their lives both personally and professionally during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Analysis of the survey data revealed three main themes regarding paramedic practitioners and the experiences they faced during the early COVID-19 pandemic response: challenges with change management; changes to day-to-day operations and professional practice; and implications for mental health and wellbeing.

Challenges with change management

Respondents often expressed difficulty in keeping up with the extent and frequency of policy changes at the beginning of the pandemic. Many respondents expressed frustration with the manner and frequency in which change was implemented.

Initially, there seemed to be an overload of information, resulting in many respondents saying they had felt ‘overwhelmed’, ‘overloaded’ or ‘constantly trying to catch up’.

Respondents also shared that many protocol changes were not synchronous across healthcare workplaces, such as hospitals and long-term care facilities, further complicating matters:

‘There were changes almost hourly with no way of knowing the changes until you reached the hospital, and the hospital staff were giving you trouble for not following procedure, but the exact same thing had been done the call before and now an hour later there was a change.’

Continuously evolving process changes led to cognitive overload, resulting in many respondents experiencing elevated stress levels.

Respondents expressed negative sentiments surrounding top-down communication. They often expressed frustration that they had not been given opportunities to provide feedback regarding changes that impacted their practice:

‘I have been handcuffed in the care I can provide, and the rationale does not make sense nor follow established best practices.’

As with many places during the pandemic, social distancing measures were put into practice within paramedic work environments.

Many respondents felt that leadership focused solely on physical safety, neglecting emotional and psychological safety. Removing management from the frontline to mitigate contact risk left some paramedics feeling abandoned:

‘I don't feel appreciated at all… Haven't seen or spoken to a manager since this began… It has changed my attitude completely! I have never felt so alone and dispensable or replaceable in all my 25 years of working.’

A lack of transparency and two-way communication led to many respondents feeling abandoned, undervalued, and powerless while vulnerably situated amid ambivalent circumstances.

On the other hand, nearly a quarter of respondents discussed experiencing good communication flow at some point during the pandemic or chose to shed a positive light on the information and training they had received.

These respondents cited multiple communication methods, including Zoom meetings, debriefs and memos, as well as the use of social media and apps specific to paramedic services.

Receiving direct, paramedic-specific updates was preferred to being sent large, non-industry-specific updates, as a paramedic-specific approach filtered out irrelevant information, reduced the barrage of emails and maximised clarity for practitioners.

Although multiple modes in which information and communication could occur were cited, face-to-face correspondence seemed to be the preferred method, as it minimised redundancy and supported consistent messaging. Respondents had positive comments regarding this, and shared how their workplace provided up-to-date information and outlets for two-way communication, including opportunities to share concerns with management.

Changes in day-to-day operations and professional practice

Although many respondents reported an initial decrease in call volumes, they sensed that workload increased concurrently.

Day-to-day operations shifted towards a focus on physical safety (e.g. personal protective equipment (PPE), disinfecting and cleaning). Extensive PPE requirements often left respondents with a sense of social disconnection and they felt communication with patients was hindered:

‘It is a moral injury every day. Our job is 80% communication and 20% medicine. We can't do our jobs like we want to; we can't be the people on the streets like we used to be. Every patient is a potential exposure, every call a threat. We are so tired of donning and doffing gear. We are tired.’

The enhanced focus on cleaning and safety processes paired with the reduced sense of social connection resulted in varying sentiments for respondents, ranging from a diminished sense of professional value to experiences of moral injury.

Concerns surrounding PPE were at the forefront of many discussions. Early on in the pandemic, there were worries about access to adequate stocks of PPE; later, this transitioned to fear that the quality of available PPE was insufficient.

A sizable portion of the respondents (n=74) felt that they did not have access to the PPE they needed to perform their duties safely. A shortage of N95 masks was reported multiple times (n=24) in varying jurisdictions, at times resulting in respondents having to reuse masks intended for single use.

Concerns surrounding PPE evolved into frustration surrounding the time it took to don and doff it properly, at times delaying patient care in high-acuity situations.

Respondents also commented how hot and uncomfortable PPE was to wear throughout the summer months; two mentioned developing heat exhaustion while others shared experiences of difficulty in breathing.

Although acknowledging the necessity of PPE, one Ontario respondent described wearing PPE in the heat of summer as ‘torturous’, highlighting the reality that paramedics are required to wear PPE in a range of community settings outside a climate-controlled hospital or clinic:

‘PPE affects everything, I'm too exhausted to even describe the effort, heat and communication issues I've been dealing with for the past 3 months.’

With many respondents feeling exasperated, the various issues surrounding PPE were mentioned repeatedly:

‘PPE fatigue, pandemic fatigue, compassion fatigue [are] all prominent. [There is] a lot of negativity due to procedure changes that often conflict with the previous. Conflicting directions. Fuses are short, nerves are frazzled, people are breaking.’

On a positive note, a notable portion of respondents expressed confidence in their ability to care for patients presenting with symptoms of COVID-19. Their confidence was often attributed to standard training and job experience, often referencing their training to care for patients infected with other transmissible diseases related to other pandemics/epidemics, such as SARS, Ebola and H1N1.

In contrast, other respondents expressed concern or a lack of confidence in providing such care. They expressing wariness and often noted concerns surrounding key changes to their scope of practice, especially pertaining to restricted or prohibited aerosol-generating medical procedures.

Changes to practice often left paramedics feeling stripped of their toolbox, resulting in a sense of disservice to patients. Although changes were implemented to reduce the risk of transmission of COVID-19, many respondents relayed a sentiment of discontent with these changes.

Changes to patient care protocols limited the medications and treatments that paramedics could administer:

‘At work, I feel like I experienced some moral injury while not being able to provide certain treatments to patients in severe distress (due to risk of COVID-19 transmission) and [by] taking longer to respond to everything to ensure both my own and partner's [colleague's] safety.’

‘My biggest change, which is the hardest, is not being able to treat the [short-of-breath patient] with regular procedures. For a while, we had nothing to provide them, medical wise. It was a disaster and very hard to live with.’

A decrease in patients being transported to the hospital, especially early in the pandemic, was also reported. Some respondents felt as though patients who truly needed transport were avoiding or delaying care as they were apprehensive of going to the emergency department (ED) in fear of contracting COVID-19 or burdening the healthcare system.

Conversely, others shed a positive light on the decrease in patient transport, claiming these patients could be better addressed by a family practitioner rather than being transported to the ED.

Implications for mental health and wellbeing

Negative impacts on mental health were frequently discussed when respondents were asked to describe how working during the COVID-19 outbreak had affected them personally.

Respondents shared experiences of increased stress, fear, anxiety, isolation and frustration. Others were negatively affected financially through loss of working hours on household income. Fewer than one in four respondents cited no significant impact, and a very small percentage mentioned a positive impact.

Many respondents reported feeling isolated during the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, whether from family, friends or the community at large. Respondents reported feeling alone and unsupported. Some directly related their sense of isolation to social distancing measures:

“[I] miss hugging friends and coworkers. [I have] negative energy and increased stress and some new-onset depression.’

Some respondents depicted emotionally taxing events (one so strong that it resulted in a post-traumatic stress disorder claim being submitted) when sharing how working during the COVID-19 outbreak impacted them personally.

Several mentioned no longer enjoying their job, feeling dispensable and overworked, and experiencing increased emotional distress from treating patients in a pandemic setting.

Those who elaborated related their stress to multiple factors. These included but were not limited to the donning and doffing of PPE, extra time needed for cleaning, constant policy changes, an overwhelming number of communications, worry about infecting family members and a restricted scope of care:

‘[It is] much more stressful. [Stressful] having to reuse PPE. Stressful having to gown up on most calls. Tensions [are] growing at the station between coworkers due to frustration, not with each other but with constantly changing rules and practices. [I] worr[y] all the time about taking COVID home to my family. It has not been good.’

Nearly a quarter of respondents discussed the toll perpetual hypervigilance was having on their wellbeing. Some said they understood the need for increased measures and awareness to ensure a safe work environment, while simultaneously reflecting on the potential seriousness of simple mistakes and the emotional toll the added responsibility was having.

A respondent with >10 years of experience shared how working throughout the outbreak had impacted them personally:

‘Some days, it's like walking on eggshells. It's an emotional roller coaster. It's a constant worry [over] if we have done enough and have been diligent enough to not take this home to our kids. Coworkers on edge, needing support, sticking together one call at a time. It feels very volatile. Anxiety creeps in often and a sense of being overwhelmed is almost a daily thing… To be honest, it's draining, being that overwhelmed myself, and then going on calls and comforting people who are dismissive of the rules regarding the virus, questioning us, downplaying what we do out here, etc.’

Many respondents reported a sense of exhaustion, burnout or loss of confidence as a practitioner. Some respondents shared a diminished sense of value in practising as a paramedic, while others shared experiences of moral injury associated with restricted scopes of practice.

When asked about any changes in their workplace culture or environment during the COVID-19 pandemic, many respondents reported a negative change in mood and low morale. Many respondents used terms such as ‘stressful’, ‘grumpy’, ‘exhausted’, ‘fatigue’, ‘fear’, ‘tension’ and ‘anxiety’ when discussing the workplace culture.

A sense of isolation paired with low morale was further exacerbated by a loss of emotional outlets. Respondents frequently reported that most of their emotional outlets and ways to unburden themselves from the intensity of their profession (such as going to the gym) were not accessible because of restrictions. Many respondents reported taking up unhealthy habits, such as increased alcohol consumption, as coping mechanisms.

Tensions surrounding opposing views of the outbreak were also reported. Respondents shared how some practitioners were apt to take all the recommended precautions very seriously while others felt the outbreak did not warrant any action or change. At times, opposing views created divisions between coworkers:

‘Crew members all seem to have different ideas about what precautions we're supposed to take, and some don't seem to take the new PPE guidelines seriously at all, which creates tension. There are different ideas about whether to social distance when at the station… and how to accomplish this with limited space.’

A small proportion of respondents (3%, n=13) noted positive impacts related to working through the pandemic. They found practising as a paramedic during the outbreak to be rewarding, and reported feeling valuable and discovering their own resilience.

One respondent expressed pride in the way their paramedic service collaborated with surrounding services and the provincial health authority:

‘[The COVID-19 outbreak] sparked new ideas, highlighted collaboration, bolstered relations and partnerships… both personally and professionally, which resulted in renewed [personal] inspiration in the career.’

Respondents who reported positive outcomes tended to focus on strengthened relationships between practitioners because of having to watch out for each other while working through extraordinarily difficult times.

Another positive outcome brought to light by respondents was the strength that community support provided. Public displays of appreciation were found to be meaningful to paramedics.

One respondent (R131, BC) expressed gratitude for the musicians who had performed outside the hospital and felt comforted by the church bells ringing in support of healthcare providers.

Other common examples included the appreciation of material support from the public, including unsolicited food donations, presents and gift cards. Feelings of being noticed and appreciated by the public like never before were also mentioned by respondents.

Discussion

This study findings show that the COVID-19 pandemic did not create areas of concern but exacerbated existing issues.

Although historically a protocol-driven vocation with limited responsibility and autonomy, paramedicine has evolved to include a broad scope of practice that requires significantly greater clinical decision-making and accountability (Simpson et al, 2017).

While paramedicine remains in the relatively early stages of defining its professional roles and identity, both of these have quickly become increasingly complex and ambiguous (O'Meara, 2009; 2011).

A 2012 study exploring UK and US paramedic perspectives found that honest relationships with patients with a focus on patient benefit and a strong orientation to timely treatments were key components of paramedic professional identities (Johnston and Acker, 2016). Simpson et al (2017: 5) contended that paramedics saw themselves as ‘highly trained to manage patients with life-threatening conditions and it [is] evident that everything around them, culturally and organizationally, reinforces that this is what they are here to do’.

Overall, paramedic professional identities have been found to closely align with patient care procedures and interventions, a diverse technical skill set and an affinity for thrill-seeking combined with a strong sense of duty to care (Trede, 2009; Johnston and Acker, 2016; Munro et al, 2018).

In some cases, problems around decision-making and job satisfaction occur when their work and roles stray from providing high acuity care. Simpson et al (2017) reported that paramedics tended to feel ‘frustrated’ and ‘tired’ when attending a significant proportion of low-acuity calls that do not reflect their expectations, which often results in burnout and fatigue.

During the pandemic, paramedics experienced significant changes in their day-to-day work and professional practice. Many respondents reported frustration and a decrease in the sense of their own value or professional contribution as call volume decreased and more emphasis was placed on cleaning and disinfecting stations and equipment.

Interventions that practitioners perceived as essential for patient care and part of their professional skill set (such as intubation and nebulising medications) were removed from their toolbox. In many cases, donning PPE was perceived as delaying timely patient care.

In addition, survey respondents identified that PPE created significant difficulties in communicating with patients, reaffirming how prominent interpersonal skills are in paramedicine (Williams, 2012; Ford-Jones and Daly, 2020; McNamara, 2021).

Many of these changes in day-to-day work and professional practice resulted in a professional identity misalignment, which was distressing to practitioners. In some cases, practitioners felt they were personally providing a disservice to patients, resulting in experiences of ethical dilemmas and moral distress.

Mental health impacts described by paramedics during the pandemic encompassed both the high-intensity and critical-incident nature of paramedic work as well as the day-to-day operational and organisational stressors within paramedic services.

While specific demands related to the pandemic were highlighted by this study, the findings also strongly align with pre-existing literature that illustrates the consequences of day-to-day stressors and the vital importance of management's response to paramedics' distress and related needs (Lawn et al, 2021). Organisational and occupational factors including shift work, workload and demands, limited downtime, hierarchical supervision and a lack of recognition have substantial impacts on paramedics' wellbeing. Findings from this study align with previous research highlighting the long-term implications of day-to-day operational and organisational stressors on mental health, which in many circumstances resulted in more significant consequences than directly witnessing critical incidents (Donelly, 2012; Lewis-Schroeder et al, 2018; Lawn et al, 2020).

Although concerns regarding mental health and wellbeing existed before to the pandemic, the findings of the present study indicate that they have been exacerbated throughout the pandemic because of additional strains and demands.

Providing attention to practitioner wellbeing and the stressors that impact their day-to-day work life are essential in preventing, supporting and assisting in the recovery of paramedics experiencing distress both during and beyond the pandemic.

Recommendations

Paramedic service administrators need to act on operational and organisational stressors to mitigate distress and circumvent the negative mental health outcomes being experienced by practitioners whenever possible. This study found that the COVID-19 pandemic did not create areas of concern but exacerbated existing issues.

Supporting the mental health of paramedic practitioners in a proactive rather than reactive manner is imperative for professional longevity and practitioner wellbeing.

Our findings also demonstrate the need for an ethical decision-making framework to support the profession in during uncertainty. Some stress and grief expressed by respondents were the result of poor communication or decision-making rooted in audit culture, which asked practitioners to act in a manner that was misaligned with their personal beliefs or values.

As greater clarity around the role of paramedics is developed, it is important that educators clearly communicate the reality of the work to student paramedics to ensure their expectations are aligned with reality to reduce future stress, burnout and discontent. High-acuity care makes up a small proportion of paramedic practice while lower acuity, interpersonal work and repetitive operational tasks (such as cleaning) continue to grow in proportion. Realistic expectations should be communicated clearly and as early as possible to individuals entering the field of paramedicine.

Limitations

This study was limited because data were collected exclusively through survey responses. While the open-ended questions were designed to cover a wide array of topics and give participants' an opportunity to express themselves fully, answers were constrained by the respondent's perception of the intent of the question.

The survey was also only available in English, and as such may not fully represent the experiences of French-Canadian paramedics. Because of there were no survey respondents from the Northwest Territories and Nunavut, this study also may not fully represent the experiences of northern Canadian paramedics. However, saturation of data with consistent repeated themes across provinces was achieved.

The number of respondents per province was not proportional to the number of practitioners per province, so certain provincial experiences may require more in-depth exploration.

The findings discussed in this article were collected throughout the first wave of the outbreak. This study continued to collect survey responses as COVID-19 evolved and future work will examine the continued experiences of Canadian paramedics throughout the initial three waves of the pandemic.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the existing challenges of the evolving practice and role of paramedics. This study illustrates the lived experiences of paramedics during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada.

Many practitioners shared experiences of professional identity misalignment in light of COVID-19 as limitations placed on the scope of practice created a disconnect between practitioner expectations and reality.

Personal safety concerns and the need for persistent hypervigilance also took a toll on the mental health and wellbeing of practitioners as respondents often disclosed experiencing increased stress, fear, isolation, frustration and moral injury. Surprisingly, these experiences did not seem to be correlated to the regional number of active COVID-19 cases at the time of data collection. Instead, the experiences of paramedics during the pandemic were informed by their paramedic services' historical work environment, culture and ongoing relationships with leadership.