This paper aims to provide data from callouts to Nepal Ambulance Service (NAS) to aid future research into Nepali prehospital care, and identify any trends and areas within NAS that may benefit from further training within NAS. To meet the aims, NAS callout data from a 12-month period was collected and analysed.

NAS uses trained emergency medical technicians (EMTs) to lead ambulance-based care. NAS is a non-profit organisation dedicated to providing first-class care to Nepalese people of all backgrounds.

Throughout the world, patients with life-threatening conditions depend on the timeliness and skill of prehospital clinicians to help prevent avoidable mortality/morbidity. Al-Shaqsi (2010) says any emergency medical service (EMS) is ‘an integral part of any effective and functional health care system’. The same is true in Nepal.

Historically, prehospital care in Nepal has been minimal and underdeveloped (Pandey, 2016). The literature on Nepali prehospital care is limited, as it is on many other countries of similar socioeconomic status (Aluisio et al, 2019). Ambulance services exist but there are no formal national regulations governing them (Bhandari, 2020). A study in 2017 of the eastern Nepal region found the fewer than a quarter stocked adequate emergency medical equipment, and more than half of staff had no basic first aid training (Acharya et al, 2017). Because of this, many private ambulances provide only transport.

Since its establishment in 2011, NAS has strived to improve this through providing emergency care with trained staff to local communities across several areas of Nepal.

NAS now employs many staff, including EMTs, pilots, physicians, call takers/dispatchers, administrators and managers. The dispatch centre is in central Kathmandu and operates ambulance stations at seven locations in Pokhara, Chitwan and Butwal, as well as four in Kathmandu. Operating from these areas allows NAS to see and treat a plethora of people and transport patients between hospitals.

Methodology

A retrospective hand search of the NAS database, which holds a digital record of the calls received and attended by NAS, was carried out.

Permission was sought from the medical director for NAS to acquire the anonymised data from the NAS computer system for research purposes. The data collected by the authors does not breach the privacy people using NAS. NAS is a teaching and learning institute and service users understand that the data collected may be used for teaching and learning as well as for research purposes.

All recorded cases attended by NAS from 1 August 2018 to 31 July 2019 (12 months) were included in the search.

Cases were first divided into either primary or secondary categories. Primary cases involved service users contacting NAS from within the community and NAS staff were the first formal practitioners in attendance. Secondary cases were hospital-to-hospital transfers.

Cases were then subcategorised according to the chief presenting complaint as documented on the NAS database. Key words were used as inclusion criteria to match NAS chief complaints (Joint Royal Colleges Ambulance Liaison Committee, Association of Ambulance Chief Executives, 2019) to a set medical category (Table 1). Chief complaints that did not meet inclusion criteria were excluded from the overall case total.

| Chief complaint category | Key words | |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular | Cardiac arrest |

Cardiac arrhythmia |

| Respiratory | Respiratory arrest |

Pulmonary embolism |

| Neurological | Transient ischaemic attack |

Parkinson's disease |

| Ear, nose and throat (ENT)/oral | Bleeding from nose |

Epiglottitis |

| Eyes | Retained foreign body in eye |

Pain in eye |

| Gastrointestinal | Abdominal pain |

Vomiting |

| Skin | Minor wound |

Infection of skin and/or subcutaneous |

| Non-traumatic musculoskeletal | Backache/back pain |

Ankle pain |

| Genitourinary | Urinary tract infectious disease |

Disorder of menstruation |

| Pregnancy & Labour | Postpartum haemorrhage |

Resuscitation of neonate (procedure) |

| Endocrine, systemic and infection | Anaphylaxis |

Jaundice |

| Trauma | Major trauma |

Fracture of rib |

| Mental health | Psychotic disorder |

Delusions/hallucinations |

| Substance misuse | Alcohol intoxication | Intoxication caused by recreational drug misuse |

| Altitude sickness | Altitude sickness | |

Seventy-four cases were excluded from the study for the following reasons:

Results

A total of 5486 cases were sourced in the NAS database using the above methodology and included in this study. The results are shown in the online appendix under the following headings:

| Month | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conditions | Primary or Secondary | Aug-18 | Sep-18 | Oct-18 | Nov-18 | Dec-18 | Jan-19 | Feb-19 | Mar-19 | Apr-19 | May-19 | Jun-19 | Jul-19 |

| Cardio | Primary | 23 | 24 | 29 | 13 | 18 | 24 | 13 | 21 | 10 | 28 | 16 | 31 |

| Cardio | Secondary | 31 | 32 | 39 | 26 | 35 | 45 | 30 | 44 | 45 | 41 | 37 | 72 |

| Respiratory | Primary | 15 | 37 | 30 | 34 | 34 | 40 | 52 | 63 | 48 | 60 | 37 | 32 |

| Respiratory | Secondary | 32 | 39 | 33 | 32 | 38 | 55 | 68 | 53 | 51 | 48 | 62 | 66 |

| Neurological | Primary | 29 | 30 | 23 | 19 | 26 | 31 | 20 | 45 | 41 | 40 | 29 | 33 |

| Neurological | Secondary | 20 | 18 | 34 | 30 | 39 | 33 | 19 | 48 | 31 | 34 | 29 | 43 |

| ENT/Oral | Primary | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 2 |

| ENT/Oral | Secondary | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Eyes | Primary | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Eyes | Secondary | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Gastrointestinal (GI) | Primary | 34 | 46 | 32 | 38 | 15 | 21 | 28 | 55 | 45 | 38 | 38 | 44 |

| Gastrointestinal (GI) | Secondary | 24 | 8 | 21 | 21 | 18 | 19 | 17 | 26 | 28 | 23 | 31 | 35 |

| Skin | Primary | 5 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 6 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Skin | Secondary | 1 | 5 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 7 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 2 |

| MSK (Non-Trauma) | Primary | 5 | 11 | 4 | 13 | 6 | 8 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 7 | 7 | 9 |

| MSK (Non-Trauma) | Secondary | 1 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Genitourinary | Primary | 13 | 11 | 9 | 15 | 6 | 10 | 9 | 7 | 20 | 10 | 6 | 10 |

| Genitourinary | Secondary | 4 | 3 | 6 | 8 | 12 | 8 | 4 | 5 | 15 | 18 | 7 | 9 |

| Pregnancy and Labour | Primary | 24 | 31 | 24 | 29 | 28 | 11 | 15 | 16 | 22 | 9 | 14 | 27 |

| Pregnancy and Labour | Secondary | 8 | 3 | 8 | 7 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Endo/Systemic illness/Infection | Primary | 30 | 30 | 32 | 18 | 26 | 27 | 17 | 20 | 15 | 25 | 31 | 19 |

| Endo/Systemic illness/Infection | Secondary | 14 | 20 | 11 | 12 | 8 | 16 | 6 | 11 | 18 | 16 | 17 | 25 |

| Trauma | Primary | 33 | 44 | 48 | 49 | 47 | 43 | 29 | 50 | 64 | 62 | 55 | 36 |

| Trauma | Secondary | 32 | 37w | 33 | 30 | 48 | 28 | 31 | 37 | 33 | 29 | 39 | 39 |

| MH | Primary | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| MH | Secondary | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Substance misuse | Primary | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Substance misuse | Secondary | 5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Altitude sickness | Primary | 6 | 1 | 6 | 12 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 9 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Altitude sickness | Secondary | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 395 | 437 | 430 | 425 | 420 | 443 | 380 | 517 | 516 | 507 | 469 | 547 | |

| Chief complaint category | Total number (%) |

|---|---|

| Respiratory | 1059 (19.30%) |

| Trauma | 976 (17.79%) |

| Neurological | 744 (13.56%) |

| Cardiovascular | 727 (13.25%) |

| Gastrointestinal | 705 (12.85%) |

| Endocrine, systemic and infection | 464 (08.46%) |

| Pregnancy and labour | 304 (05.54%) |

| Genitourinary | 225 (04.10%) |

| Musculoskeletal non-traumatic | 107 (01.95%) |

| Skin | 69 (01.26%) |

| Altitude sickness | 42 (00.77%) |

| Ear, nose and throat/oral | 19 (00.35%) |

| Eyes | 19 (00.35%) |

| Substance misuse | 16 (00.29%) |

| Mental health | 10 (00.18%) |

Analysis and discussion

Overarching trend

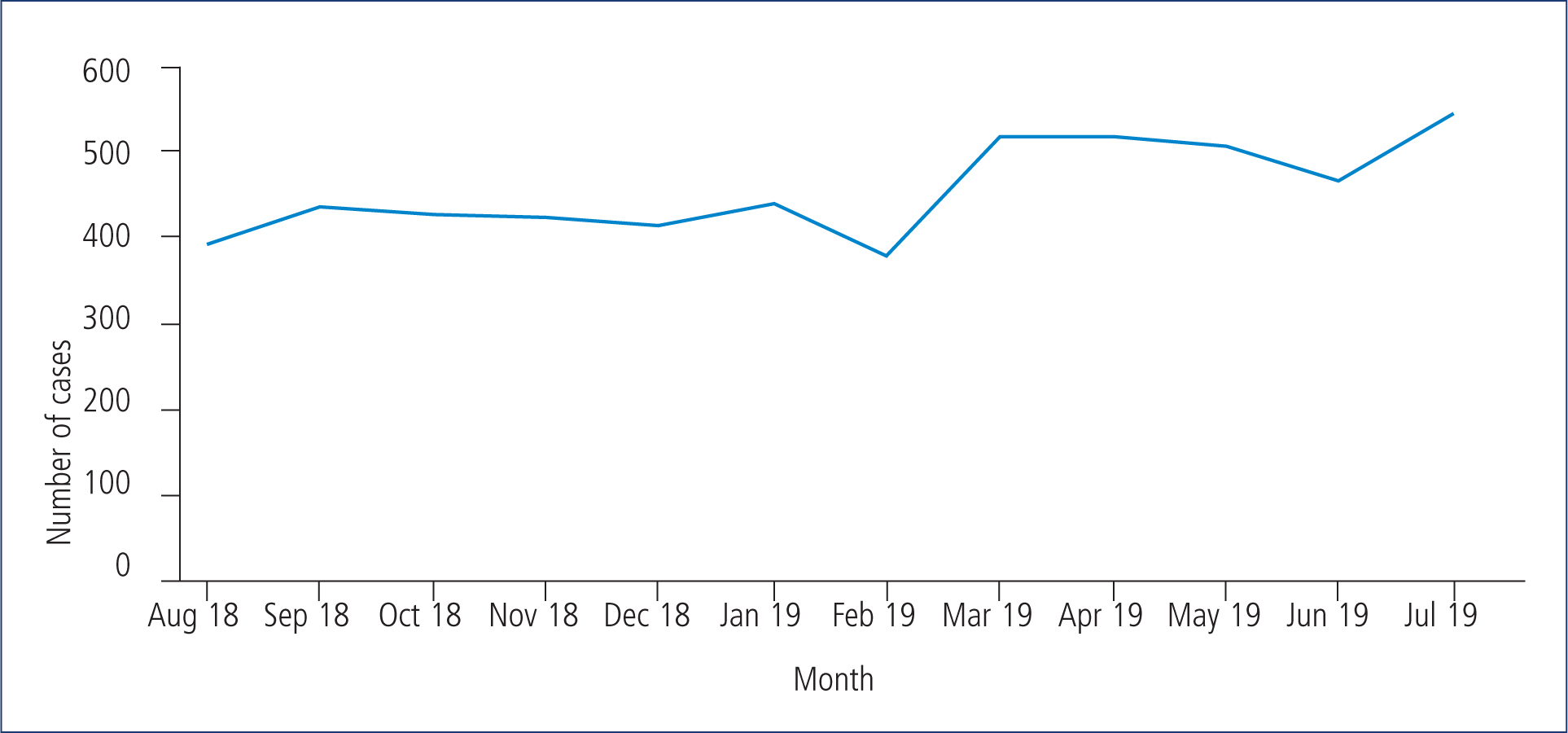

The first observation that can be made from the results is that there is a general upward trend of NAS cases numbers throughout the trial months. In July 2019, 152 more cases were logged than in August 2018, an overall increase of 38.48%. This increase is fairly uniform and consistent month-on-month, except for in February 2019, which displays an unexplained reduction.

In 2013, NAS was dispatching a mean of nine ambulance responses daily (Walker et al, 2014). The NAS database shows that this number had risen to an average of 15 EMT ambulance responses per day within our study period. This increase could be a result of greater public awareness and the growing reputation of NAS.

It could be argued that a general increase in illness among the Nepali population from an unknown source could have caused the increase in patients treated by NAS. However, this seems unlikely as most medical categories increase uniformly rather than systemic illness only.

Primary versus secondary cases

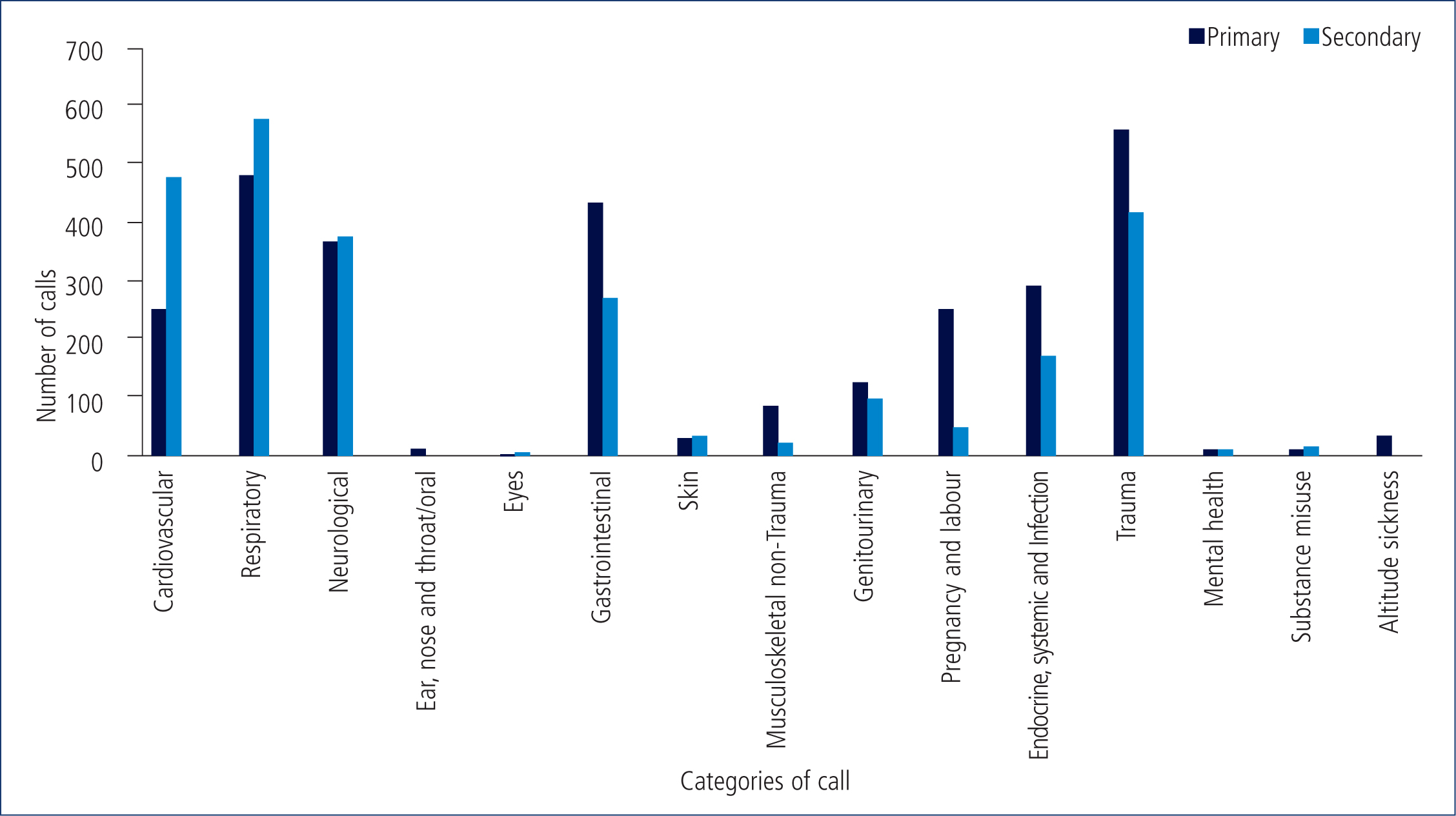

Primary cases (2946) accounted for 53.7% of cases and secondary cases (2540) accounted for 46.3%, a difference of 7.4 percentage points. This shows that NAS is used at similar levels for primary and secondary cases. The reason for this is unclear, as is the reason why slightly more primary than secondary cases are seen.

Overall largest category

In primary and secondary cases combined, patients complaining of respiratory problems are the most numerous. The data from this study alone are inadequate to make any categorical judgment as to the cause.

However, it is likely that the high levels of air pollution in the Kathmandu valley have contributed to the number of respiratory complaints (Saud and Paudel, 2018). It is also possible that high levels of smoking tobacco in Nepal (Shrestha et al, 2019) have contributed.

Respectively, air quality and tobacco use have remained the second and third highest risk factors for disease in Nepal from 2009 to 2019 (GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators (GBD), 2020a). This systemic analysis also found that, in 2019, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) was the leading cause of death and disability in Nepal (GBD 2020b).

This is not the case for many countries with a similar socioeconomic status, such Rwanda where COPD is the 14th highest cause. Even in neighbouring India, COPD is the third biggest cause of death and disability (GBD, 2020b).

The presence of other respiratory conditions in Nepal such as tuberculosis should also be taken into account as they can also lead to COPD (Bansal et al, 2019).

Largest primary category

Over the data collection period, the most common reason for a primary case was trauma. Given the nature of physical trauma, often being debilitating and sudden, patients often cannot get to hospital other than by ambulance. Poor road conditions, negligent drivers and an increase in vehicles on the road all may contribute to the growing number of patients experiencing trauma in Nepal (Karkee and Lee, 2016).

In their 2001-2013 epidemiology of road traffic injuries (RTI) in Nepal, Karkee and Lee (2016) report Kathmandu Valley has a higher RTI rate yet fewer mortalities than the rest of the country. Dhakal (2018) also reports that the mortality rate is lower in the capital than in other parts of Nepal. Dhakal (2018) also reports a decrease in mortality rate in the capital in comparison with other parts of Nepal.

Given that four ambulance stations are based in Kathmandu, it is possible that NAS has contributed to the improved survival rates in recent years.

Smallest category

Mental health cases were found to be the least common presenting complaint during the study period, with just 10 cases. This is very different from Western culture, where mental health problems are widely acknowledged (Kosidou et al, 2010) and are frequently attended by emergency services (Larkin et al, 2006; Roggenkamp et al, 2018).

The low number of mental health cases could be because of a lack of awareness of mental health issues or a strong taboo against such conditions (Lauber and Rössler, 2007; Aryal et al, 2019; Roslee and Goh, 2021) describe an overwhelming stigma and prevalent discrimination towards mental illness in Asia. They report that patients prefer alternative treatment and management such as a spiritual, supernatural or magical approach. These could account for the low numbers of people with mental health issues using NAS.

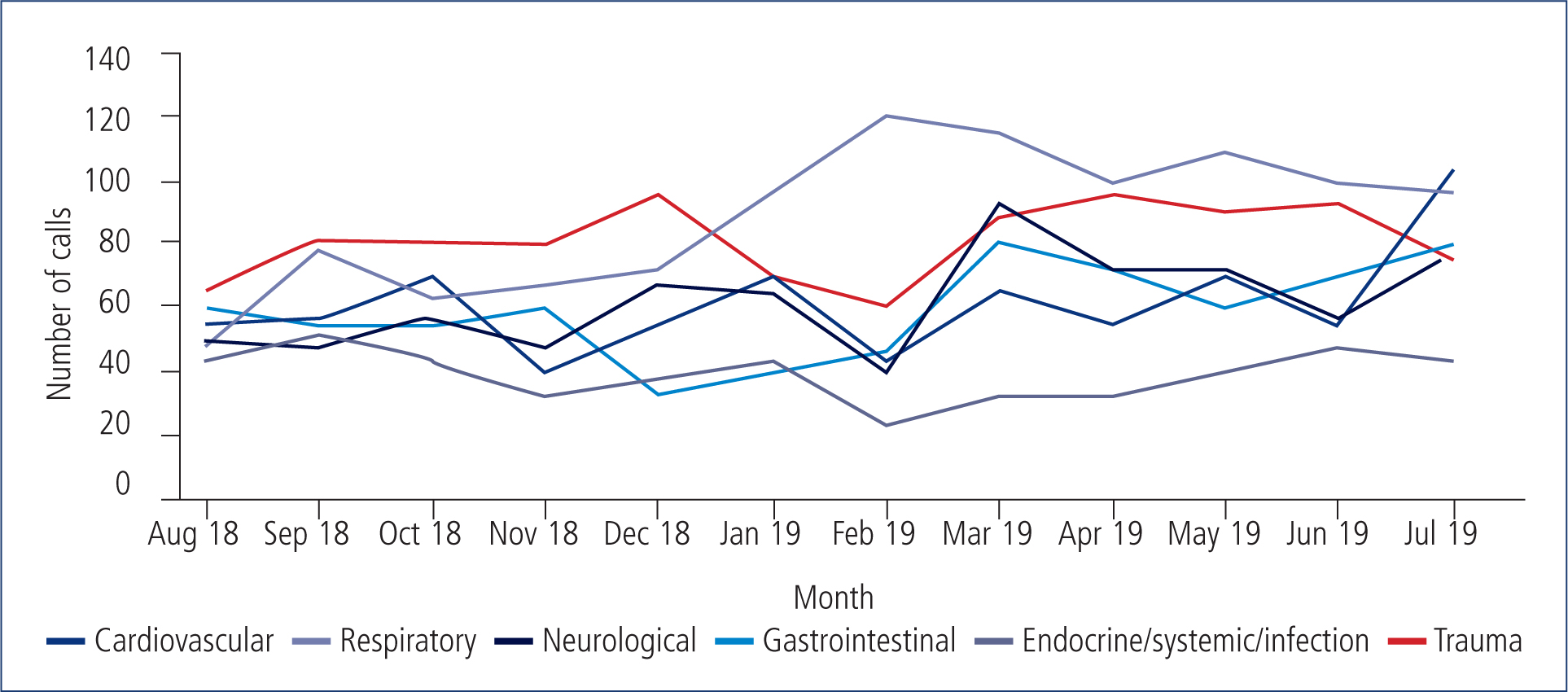

Seasonal trends

During the colder months in Nepal, the collective data shows a peak in respiratory cases. This could be because cold weather is known to exacerbate COPD (Bhandari and Sharma, 2012). Seasonal respiratory viruses such as influenza or respiratory syncytial virus (Sloan et al, 2011) may also play a part.

In contrast, trauma cases appear to decrease slightly around the same colder period. This is somewhat similar to a 9-year study in Germany by Pape-Köhler et al (2014), who found trauma to be lowest during the cold period between Christmas and the new year.

The monsoon season (June-August) did not appear to produce any obvious pattern in the data. There is, however, a peak in secondary cardiovascular cases in July 2019 of which the cause is unclear.

Recommendations

The authors have several recommendations for further research.

Patients should be surveyed on why are they are not are not using NAS services. Addressing this would create opportunities to make the service more patient centred. This could increase call volume to NAS.

Statistical data on treatments provided by NAS during callouts could be analysed to improve care.

Whether a service like NAS would be feasible on a national level could be examined.

This study collected data just months before the COVID-19 global pandemic (World Health Organization, 2021). Analysis of data on the caseload of NAS in a post-COVID-19 Nepal could offer a fascinating insight into how COVID-19 has affected NAS and the Nepali community.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study.

First, all the data were sourced from the NAS database in Nepal. Data input for this resource was done by hand, and the information was extrapolated from the database for this study also by hand, so the data are subject to human error.

In addition to the potential for human error, some case documentation on the NAS database was ambiguous and, unfortunately, could not be categorised.

Moreover, the researchers noticed that several patients had duplicate records created by administrative staff on the database. The reason for this assumed to be because some cases started as primary and then became secondary when the patient was moved to another hospital. This means that one patient could possibly account for two callouts.

Further to this, some callouts were listed as primary when the location of the call out was a hospital, raising the possibility that some secondary cases were inadvertently labelled as primary.

These potential flaws were not taken into consideration when calculating the total number of patients NAS saw within the 12 months studied.

Additionally, some patients may fall into more than one category. The reality of patient care is complex and diverse. For example, mental health issues may present with a chief complaint of poisoning, intoxication or even trauma, if the patient had self-harmed. However, using this study's methodology, these patients would be categorised as GI or trauma instead of mental health cases.

Finally, accessible literature around Nepali prehospital care was extremely limited at the time of writing so in-depth comparison to previous findings was not possible within this analysis.

Conclusion

This study found a rise overall in total cases treated by NAS within a 12-month period, with respiratory and trauma cases being having the highest numbers. This rise in cases is most likely because NAS is growing more popular within Nepal.

Based on the findings of this paper, it would seem that NAS is set to continue its upward trajectory of callouts. Further research on this service is warranted.